In our session this week we looked at AI image generation, in particular, how the tools are trained by using a huge number of datasets created by scraping data from the internet; the impact of this form of training including bias and breach of IP rights; its ethical and environmental impact; and the effect on us, as artists, in terms of our own relevance, the potential use of our work as training input, and our ability to use AI to create output in our artistic practice.

It is astonishing how quickly this area is developing. However, until it reaches a stage whereby AI can create an image in which there is human emotion and imperfection, we probably won’t become obsolete just yet.

Being from a legal background, I was particularly interested in the issues that generative AI tools have thrown up in terms of intellectual property rights. The main issues seem to be the potential breach of copyright in both the collection of data for training, and the output created, as well as the question as to who owns the output and whether it should itself be protected by copyright.

The problem with data scraping is that whilst the data is widely available in the public domain, this doesn’t mean that it can be copied and used without limitation (in the UK the only current exception to copyright protection in respect of text and data mining is for non-commercial research). This could mean that any images of artwork which I have produced, and which are publicly available on the internet, could be used to train generative AI and, consequently, could possibly form part of an output image generated by a third party, despite the copyright in the original image belonging to me. It’s a contentious issue, and there is lots of litigation going on at the moment across numerous jurisdictions including the UK and the US. In the UK, Getty Images has taken action against Stability AI for using millions of Getty Images to train its Stable Diffusion tool. Claims have similarly been made in the US against Meta, Midjourney and Anthropic, amongst others.

Another related issue, is that generative AI platforms will generally reserve the right to use any input or prompts from users to improve the performance of the tool, which could have implications in terms of privacy and confidential information.

Whilst it is unlikely that generative AI will create images which are exact reproductions of copyrighted images which have been used for training or as input, should there be sufficient similarity, there may be a potential breach of IP, but this will depend on an assessment being made in each case. It will also depend on being able to pinpoint where the content has come from, bearing in mind the huge number of resources across many jurisdictions. As part of their case with Getty Images, Stability AI are relying on the defence of fair dealing, as well as that of parody, caricature and pastiche i.e. that the image generated is not a replacement for the original image but a pastiche, and so it does not affect the market for the original image or its value. It probably didn’t help that in this case that some of the output images contained parts of the Getty Images watermark. This case is destined to be a trailblazer, but we won’t know the outcome until the middle of next year.

It is theoretically possible that an image created by prompts and inputs from a user of generative AI is capable of being owned by the user. However, the user cannot assume that they own the content or that they are able to use it as they wish. Firstly, who is the owner of the created image varies from country to country. Secondly, the terms and conditions of the platform may determine ownership and rights e.g. Midjourney’s terms and conditions, whilst providing that the user owns the created image, state that by using the service, the user grants Midjourney and all its affiliates etc. extensive rights in relation to the output image to reproduce and sub-license it etc. at no charge, and royalty free.

In the UK, the author of original literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work owns the copyright in that work, unless it was created in the course of employment or by way of commission. There is no need for registration in order for the work to be protected, unlike in the US where it has to be registered with the Copyright Office. In fact, the UK is one of the few countries which recognise copyright protection for computer generated works. However, for the work to be original it must be the author’s intellectual creation and reflect their personality. It is not clear how this might be applied in the context of work created by AI. Furthermore, the ‘author’ is the person by whom the necessary arrangements for the creation of the work are undertaken. So, who is that? The user who specifies the prompts, or the person who created the AI tool? This issue is likely to be decided on the facts of each case, including the T&Cs of the platform.

It’s all very much up in the air, and destined to become even more complicated, the more sophisticated generative AI becomes. For the time being, as artists it would be a good idea to take the precaution of reading the small print of the platform being used, keeping detailed records of the process being used including all the prompts in response to which the image was generated.

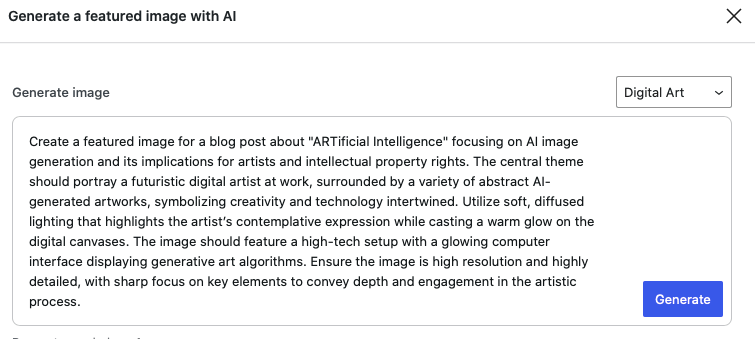

Whilst writing this post, I noticed the WordPress AI Assistant. It created the image at the top of this post after generating the following prompt based on the contents.

I’ll finish with Alan Turing’s warning which he gave in a lecture in 1951:

” Once the machine thinking method had started, it would not take long to outstrip our feeble powers. At some stage, therefore, we should have to expect the machines to take control.”