Month Jan 2025

Dialogue I

I’ve been thinking about what I can do for my submission to the Summer Exhibition.

One thing is for certain, the resource of time over the next two weeks is extremely limited, what with the deadlines for my study statement, curation of my blog and something for the interim show in March, all of which take precedence. In previous years I’ve given a lot of thought and time to my entry and got precisely nowhere, so this year I’m going to do something different. It will be interesting to see whether rejection feels different depending on how much time has been invested. I’m going to follow the philosophy of Gino D’Acampo – minimum effort, maximum satisfaction – have a bit of an experiment and not get too hung up about it.

I’ve put my initial thoughts into a mind map although, to be honest, when I’ve been round the exhibition in previous years, I’ve struggled to see the relevance of some works to the theme.

There are quite a few ideas to consider:

- I quite like the idea that ‘dialogue’ literally means ‘through words’ – words in the work itself/ posing a question?

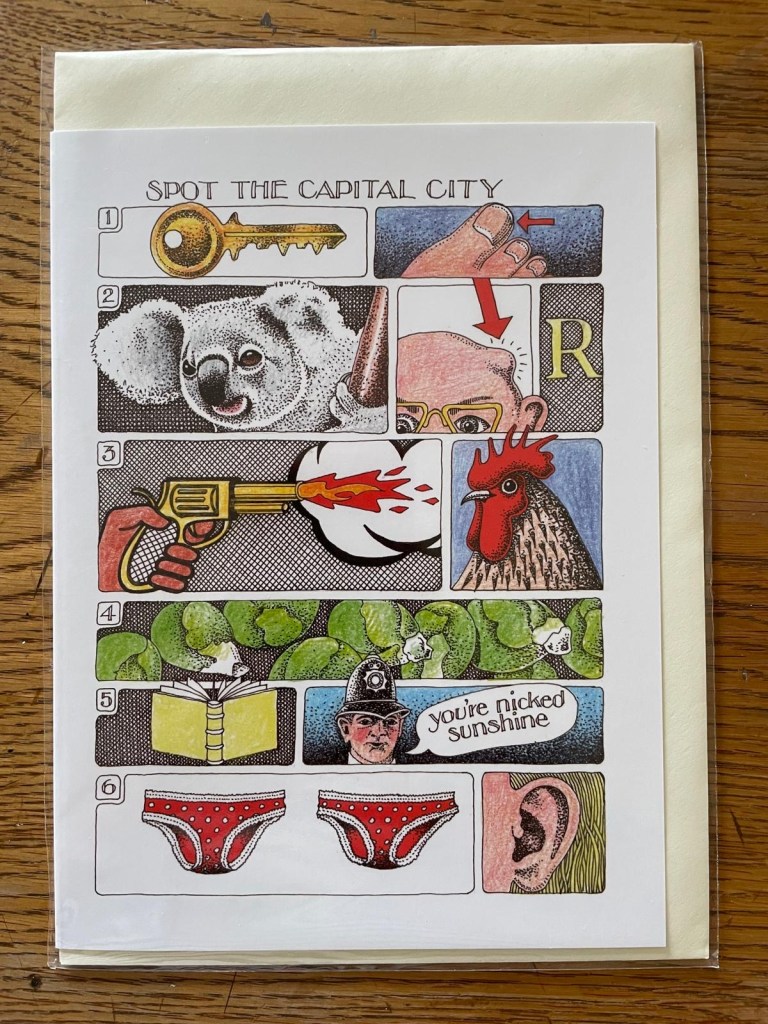

- What about the ability of images to convey phrases and words? One of my favourite TV programmes when I was a teenager was Catchphrase, in which contestants had to guess the phrases being represented by a short animation. Those were the days when it was hosted by Roy Walker – much better than the revival hosted by Stephen Mulhern. A while ago I was looking for a birthday card, and I came across this one. It took me ages to get out of the shop – I tried to solve the clues, the women behind the counter had been trying to solve them all morning, it seemed everyone in the shop wanted to have a go.

- Exchange – does a dialogue have to be continuous or can there be pauses eg written dialogue in letters, email etc? Can it be in different forms eg verbal met with non-verbal response?

- Dialogue between the viewer and the work?

Anyway, I’m going to have a quick look to see how other artists have dealt with the subject of dialogue, whilst giving it all some further thought.

ARTificial Intelligence II

I’ve just been watching ‘Sunday with Laura Kuenssberg’ and one of her guests was Baroness Beeban Kidron, a former film director who was appointed as a crossbench peer. She specialises in protecting children’s rights in the digital world, and is an authority on digital regulation and accountability.

The topic of conversation was Labour’s plan to change copyright law so that tech companies can scrape copyrighted work from the internet to train their generative AI tools free of charge, unless individual creatives decide to opt out. They are proposing what is, in essence, legalised theft.

Labour launched their AI Opportunities Action Plan two weeks ago. They intend that the UK should become a world leader in AI with the amount of computing power under public control being increased 20 times over by 2030. They will achieve this by making huge investments (£14bn provided by tech companies, of course!) in setting up the infrastructure needed to create AI growth zones, a ‘super computer’ as well as huge energy intensive data centres necessary to support it. Clearly this will have a significant environmental impact and is at odds with Labour’s election promise to hit its green target to create a clean power system by the same date of 2030, which some experts think was going to be difficult to meet anyway.

Apparently, this will result in the UK’s economy being boosted by £470bn over the next 10 years. This may well turn out to be Starmer’s figure on the side of the bus. Kidron commented that the small print reveals that the figure was sourced from a tech lobbying group which was paid for Google and which was arrived at by asking generative AI, and which, in any event, reflects the global, not the national, uplift in the economy.

Kidron is a vocal supporter of the option to opt-in rather than putting the onus on the individual creative to contact each of the AI companies, who are using their work, to opt out. In fact, opting-out is something that’s not technically possible to do at the moment. To this end, she has put forward amendments to the Data (Use and Access) Bill which will be debated in the House of Lords this week. She has also previously commented in the press that she can’t think of another situation in which someone who is protected by law must actively wrap it around themselves on an individual basis. I think she makes a good point, and I agree with her view that the solution is to review the copyright laws and make them fit for purpose in an AI age. The creative sector, which includes artists, photographers, musicians, writers, journalists, and anyone else who creates original content, is made up of about 2.4 million people and is hugely important to the country’s economy, generating £126bn. That money should be kept within the economy, and not be siphoned off to Silicon Valley.

Not surprisingly there has been a great deal of backlash from creatives including actors and musicians, such as Kate Bush and Sir Paul McCartney, since Labour announced their plans. As part of the segment, Kuenssberg interviewed McCartney who is very concerned as to the effect this will have, especially on young up and coming artists. He commented that art is not just about the ‘muse’ but is about earning an income which allows the artist to keep on creating. He fears that people will just stop creating because they won’t own what they create, and someone else will profit from it. AI is also a positive thing: he explained that they used it to clean up John Lennon’s voice from a scratchy cassette recording making it sound like he only recorded it yesterday, but he is, nevertheless, concerned by its ability to ‘rip off’ artists. He mentioned that there is a recording of him singing ‘God Only Knows’ by the Beach Boys. He never recorded the track; it was created by AI. He can tell it doesn’t quite sound like him, but a normal bystander wouldn’t be able to tell the difference. In a year’s time, even he won’t be able to tell the difference.

There is a petition which has been signed by over 40,000 creatives, and the Government is undergoing a consultation procedure which you can respond to with your comments online here. The consultation ends on 25th February.

So, what can we do in the meantime?

Short of going offline, which isn’t really an option, there is nothing which will ensure that our work is not used in training generative AI. Just from some cursory research, which incidentally was helpfully summarised by Google’s AI Overview, there is the possibility of using a watermark to protect images either physically (not so good for promoting work) or invisibly embedded in the image, using digital signatures, or a cloaking app such as Glaze, which was developed by the University of Chicago, which confuses the way AI sees your image by altering the pixels, or by using another of their apps, Nightshade, which alters the match between image and descriptive text.

For now, all I can do is to change my privacy settings on my Facebook and Instagram accounts to prevent Meta from being able to use data from my posts to train its own AI tools. I had to fill in a form explaining why I objected to them using the data, and I received email confirmation that they would honour my objection, but who’s to know if they do or not? Apparently, there is a website, Have I Been Trained?, which allows you to search for your work in the most popular AI image dataset, LAION-5B.

What’s possibly just as disturbing is the Government’s plan to allow big tech access to one of the biggest and comprehensive datasets in the world – the NHS. It’s all in one place, we all have an NHS number which gives access to a lifetime’s history of personal and health data. It will be done on an anonymous basis, but with enough data, even experts say it’s easy to re-identify people. No-one’s doubting the incredible possibilities that AI offers in terms of delivering healthcare, but proper safeguards are needed.

Anyway, I asked the WordPress AI to generate a header image based on its own prompt:

“Create a high-resolution, highly detailed image illustrating the theme of digital rights and AI regulation. Feature Baroness Beeban Kidron in a thoughtful pose, surrounded by symbols of creativity such as art supplies, musical instruments, and books. The backdrop should convey a digital landscape, with elements representing technology and copyright, like binary code and padlocks. Use soft, natural light to evoke a sense of seriousness, yet hopefulness. The image should be in a documentary style, capturing the urgency of the conversation about protecting creatives’ rights in the age of AI. Ensure sharp focus to highlight the intricate details in each element.”

Sorry, Jonathan – I will switch my mobile phone off for the rest of the day so I don’t have to recharge the battery, but, in the meantime, do we have much to worry about? It doesn’t even look like Beeban Kidron.

Dora The Explorer

Dora The Explorer was one of my daughter’s favourite TV programmes when she was a toddler. I don’t know how they did it, but Nickelodeon managed to give Dora the most irritatingly grating voice possible. Anyway, thankfully, this is not the Dora the Explorer who is the subject of this post.

I went to the Pallant House Gallery in Chichester yesterday morning to have a look at the Dora Carrington: Beyond Bloomsbury exhibition. I had heard of her, and had a vague recollection of having seen some of her work.

Dora Carrington certainly was an explorer of sorts: associated with, but not a fully paid up member of, the Bloomsbury Group, she explored her art as well as her relationships and sexuality. To be honest, I couldn’t quite keep up with the complexity of it all. At the heart of it was her enduring love for the gay writer, Lytton Strachey, who was 13 years older than her and with whom she set up home. At one point they lived with Ralph Partridge who Carrington (whilst studying at the Slade, she dropped the name ‘Dora’ preferring to be known by her surname) married in order to keep their ‘triangular trinity of happiness’: Partridge was enamoured with Carrington, Strachey fancied Partridge, and they all had relationships with each other (apart from Carrington and Strachey whose relationship was only ever platonic) as well as others of the same or opposite sex. It seems all and sundry found themselves hopelessly in love with Carrington, not least the artist, Mark Gertler, with whom she had a moment, but otherwise whose long-lasting passion was unrequited.

Portrait of a Girl in a Blue Jersey (Carrington), 1912, Mark Gertler (image: http://www.emuseum.huntingdon.org)

Dora Carrington, 1917, by Lady Ottoline Morrell (image: http://www.wallpaper.com)

Alas, it all ended tragically in 1932 with Carrington shooting herself in the chest shortly after Strachey died. She was 38 years old.

The last exhibition of her work was 30 years ago at the Barbican. During her life she rarely exhibited, and her work, many pieces of which she destroyed, seems to have been overshadowed by her adventurous private life and tragic death. She has been described by a former director of the Tate as being’ the most neglected serious painter of her time’.

It was a mixed bag, but there were a few pieces which caught my interest. Her early drawings and paintings of nudes were very good, but I found myself lingering in front of these.

Larrau in the Snow, 1922

Perfect Christmas card material, I really like the simplicity of this painting; its muted colours and, in particular, the composition with its recurring curved shapes of the stone walls and the use of verticals in the posts and trees in the foreground, the large tree and the church with its spire punctuating the sky in the middle ground and the mountains in the background. The positioning of the trees leads the eye up through the painting in a zig zag pattern.

Farm at Watendlath, 1921

Again, I like the composition: the path leads across from left to right, up through the farmhouse along the rear stone wall to the large ominous trees, up to the huge hills in the background which seem to squeeze out the sky. The three areas of white – the figures in the foreground, the farmhouse (and what look like sheets on a washing line) in the middle ground and the clouds in the sky in the background – break up the large areas of green preventing them from becoming too overpowering, but leaving enough areas unbroken to give a sense of being overpowered: the tall trees and hills seem to be bearing down on the woman and child, creating a feeling of foreboding, and the stillness (if they are sheets on a line, they’re not moving at all) and claustrophobia created by the tiny sliver of sky adds to the mood.

It was suggested by the blurb accompanying this piece, that its unsettling atmosphere might have reflected the turmoil which Carrington was experiencing at the time: she had gone to Cumbria on holiday with Partridge and his friend, Gerald Brenan, and they had stayed at the farm. Whilst there, she began a relationship with Brenan.

Spanish Landscape with Mountains, 1924

I was drawn to the surreal nature of this painting. Carrington made it from memory, after visiting Brenan in Andalusia, where he lived. According to the blurb, she built up the colour by layers upon layers of glazing on top of what was already a vibrant underpainting. She painted it on a cold day in March, which may have been a contributing factor to her use of colour and the sense of heat and aridity which she manages to create. There are menacing looking succulents in the foreground and a few token olive trees just behind, and these, together with the slight greenish tone to the area in from of the background mountain range, cleverly break up the large areas of warm reds and yellows which form the undulating hills in the middle ground. There is the lovely detail of the figures on horseback moving towards the viewer along the ridge on the left hand side. It has an otherworldly quality to it: apparently Carrington felt transported to another world when she visited Spain.

Lytton Strachey, 1916

“He was everything to me. He never expected me to be anything different to what I was.” This was how Carrington described Strachey, and it is apparent in this portrait of him which she painted towards the beginning of their relationship which was to last 16 years, and which survived numerous relationships on both sides. It shows Strachey deep in concentration reading a book which he is holding in his delicately painted hands, which Carrington has strangely elongated. Maybe his hands were her favourite feature, because she captures them in a detailed way, down to the highlights on his nails, even their white tips, particularly on his little finger. Or maybe she used them as a compositional device to create a dynamic and bold vertical marking the final vertical third of the painting. The image wouldn’t have the same impact if his hands were sized more realistically, and the book he is holding didn’t go off the top of the panel.

Carrington had a fascination for Victorian ‘treacle’ paintings and from 1923 began making her own which were called tinsel paintings. They weren’t very large and involved making a painting on the reverse of a piece of glass using foil from sweet wrappers and cigarette packets together with inks and oil paint. She sold them through Fortnum & Mason as a way to earn an income in the winter months to finance her serious art making. She also made them for friends: the ones below were made for Augustus John’s wife, Dorelia. Very few of the tinsel paintings survived, and one of them sold 4 years ago for £57,000.

Spanish Woman

Lily

I’m strangely drawn to them as I’ve never seen anything like them before. They have a strange luminescent quality to them and I particularly like the textures in the sky in Lily – the combination of the resplendent lily in a barren landscape reminds me of Georgia O’Keefe.

Anyway, I’ve done some further research: Dora Carrington’s life was made the subject of a film in 1995 – ‘Carrington’ – starring Emma Thompson and some other notable actors. I watched it last night. Perhaps not surprisingly, it’s a film about her, based on a book about him. I’m not sure that it managed to truly capture the complexities of her life and certainly only touched on her relationships with men, and not women. It was a tearjerker.

Whilst I was starting to write this post yesterday evening, I looked up and saw the most amazing sky through the kitchen window and had to go outside and take a photo of it. As usual, the image doesn’t really do it justice.

Prost, Vienna!

It’s taken me a while to finish this post – other things have got in the way – but I needed to complete it to make note of what I saw, and what I thought.

Whilst in Vienna, we also managed to visit the Secession Building, which was designed by the architect, Joseph Maria Olbrich, in 1898, as an exhibition space for the Secession. He was one of the founding members along with a group of artists, including Klimt, who had broken away from the traditional Künstlerhaus to pursue progressive contemporary art. The group’s motto which appears above the door is “To every age its art, to every art its freedom.” Topped by a golden cabbage comprised of 2,500 gilded iron laurel leaves, it houses Klimt’s Beethoven Frieze.

The frieze is based on Wagner’s interpretation of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony: it is a tale of humankind’s search for happiness.

I didn’t know what I was expecting really, which is a bit daft considering that I had seen pictures of it in books. I initially felt, yeah ok, but now reflecting on it I think I must have been suffering from a case of art gallery overload. It was really remarkable. It’s been relocated from its original position. It’s high up on the walls of the room, and surrounds you. The fact that you have to look up, makes viewing it an almost reverential experience. That coupled with the fact that you can listen to Beethoven whilst you admire it.

In addition to Klimt and Schiele, I saw many works by other artists, which I felt might be useful over the next year or so, some of whom I hadn’t previously come across.

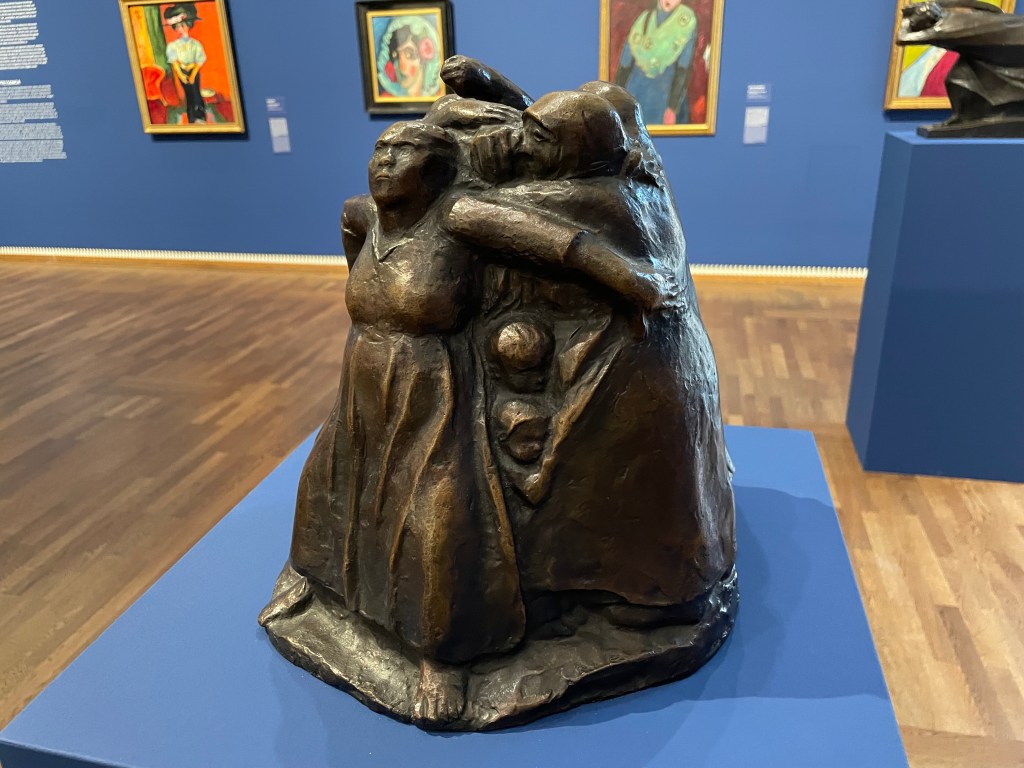

This bronze sculpture is Tower of Mothers, 1937/38 by Käthe Kollwitz. It shows a group of mothers standing together and forming a circle to protect their children, who can be seen peering out from between their skirts. The strength and determination to defend whatever the cost is beautifully captured in the postures of the figures, particularly the mother with her arms spread wide. There is no fear in this sculpture. The mothers are protecting their children from war and the horrors of war, which is poignant as Kollwitz herself lost one of her sons in the First World War, a loss she never recovered from.

These oil paintings on canvas are by Koloman Moser. Moser was a founding member of the Secession, and was primarily a graphic designer and illustrator, as well as a set designer, furniture and textile designer, and painter. I like the slight graphic quality of these paintings as well as the unusual palette – his use of what looks like a lime green gives a sickly feel to the works, and works really well with the purplish reds in the skin tones and the shroud. They appear almost luminous.

The ceramic glazed sculpture above is Insinuation, 1902/03, by Richard Lucksch. I had to resist the urge to touch it. I found myself wondering what the young men are whispering in her ears; what are they insinuating? The very title implies something negative. It reminded me how difficult it can be to navigate a true course through life, when others are constantly whispering things into one’s ears, insinuating, commenting, doubting, demoralising, chipping away.

I felt drawn to this painting, for some reason. There’s some gold; that’s a start. The skin is beautifully rendered and I like the composition: I start from the head encased in the golden square and make my way down her body with the interesting detour created by her right arm, along her legs, through her toes up towards the top right and then back to the golden square via the light coloured rectangle. It’s satisfyingly complete.

It’s Seated Woman (Marietta), 1907 by Broncia Koller-Pinells, the Austrian equivalent of radical, Laura Knight, who also challenged the taboo for women artists at the time – the nude.

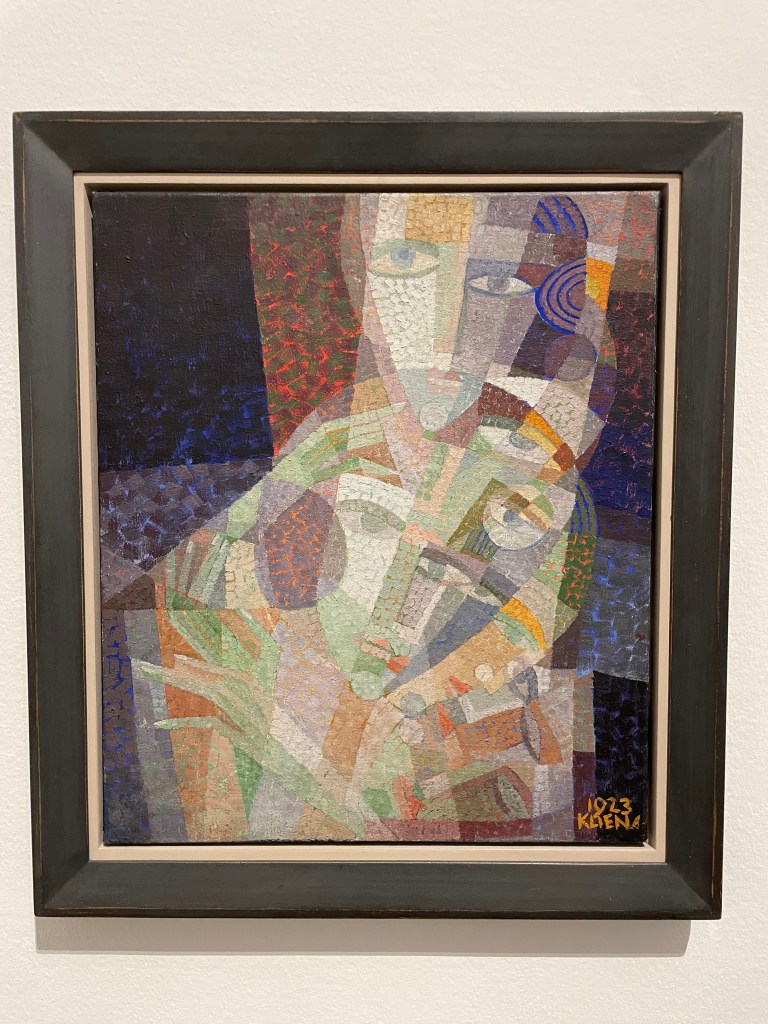

Head of A Dancer, 1923, by Erika Klien is an example of Viennese Kineticism, which was inspired by Cubism, Constructivism, Futurism, dance, music and architecture. I like the sense of movement of the head and the hands, which have also been deconstructed in parts, as well as the quite limited colour palette.

What’s not to like about a Degas figure? This one Pregnant Woman, was risqué for its time, depicting a woman in a pregnant state, and was cast in bronze after his death.

This definitely gets the award for most interesting. The Doll is from the film, My Alma – Oskar Kokoschkas’ Love to a Doll. I’ve since researched it a bit further and it really is a strange tale. Alma was Alma Mahler, Gustav Mahler’s widow. Having had her first kiss from Klimt when she was 17, she went on to have many love affairs before , during and after her several marriages. One of those affairs was with the young artist, Oskar Kokoschka for whom she became the love of his life. I think it’s fair to say he was obsessed with her. He had to go off and fight in the First World War War and whilst he was away she married a previous lover. Needless to say he was quite devastated when he returned home, after having been bayoneted in the chest, suffered a major brain injury and declared mentally unstable, to find that she had ended their relationship. So he did what all spurned lovers do, he commissioned a doll maker to make a life size doll of her providing very specific instructions as to how it should be made and what it should feel like to the touch. When she finally arrived he was a bit perturbed by the fact that her body had been covered in feathers but went on to pose her for paintings and photographs, dress her up and even take her to the opera. But eventually he resolved himself to the fact that his Alma doll wasn’t doing it for him, so he threw a party, then took her out into the garden where he chopped off her head and broke a bottle of red wine over her. I’m not sure that I’ll watch the film…

Never Drinking Coke Again

I had some free time yesterday, so I decided to try out kitchen lithography using some aluminium foil and cola.

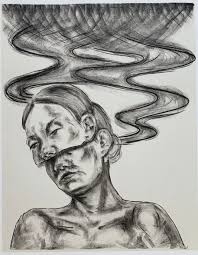

This is the first time I’ve tried it – I’ve been interested in doing it since I came across a Canadian artist who uses it in her work, in addition to other printing processes, Valerie Syposz. Her work primarily deals with self-perception and existence.

I like the surreal quality of her work, and her subject matter is relevant to what I’m exploring.

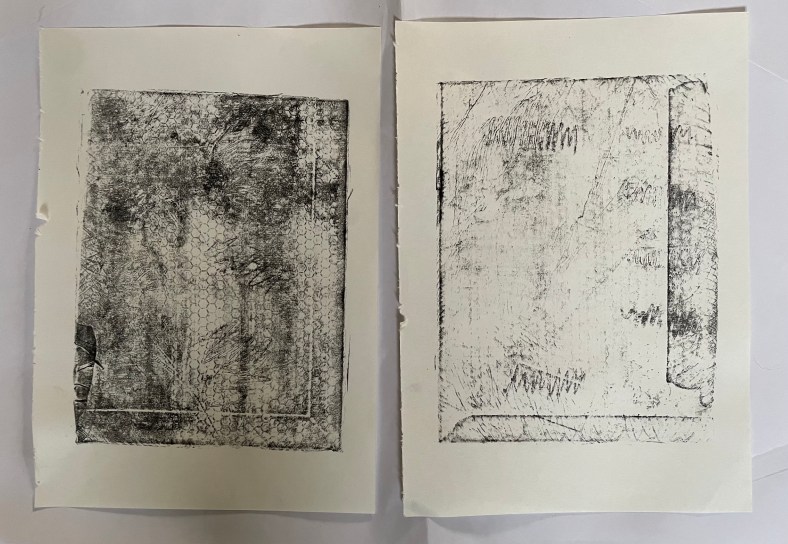

I have to be honest and say that it didn’t really go to plan. First of all, I discovered that the foil I have in my kitchen drawer has a honeycomb pattern embossed on it, and then I forgot to use the dull rather than the shiny side of the foil. I made various marks using different pencils, pens, markers, graphite sticks and pastels, but I was doomed to failure. Not wanting to go out into the cold to my shed to find some plexiglass sheets to wrap the foil around, I had used an Amazon envelope which I found in the recycling bin, which turns out had some raised edges on it. But, hey, it’s just an experiment. I also didn’t apply enough water to the plate which meant that the ink adhered to areas it shouldn’t have.

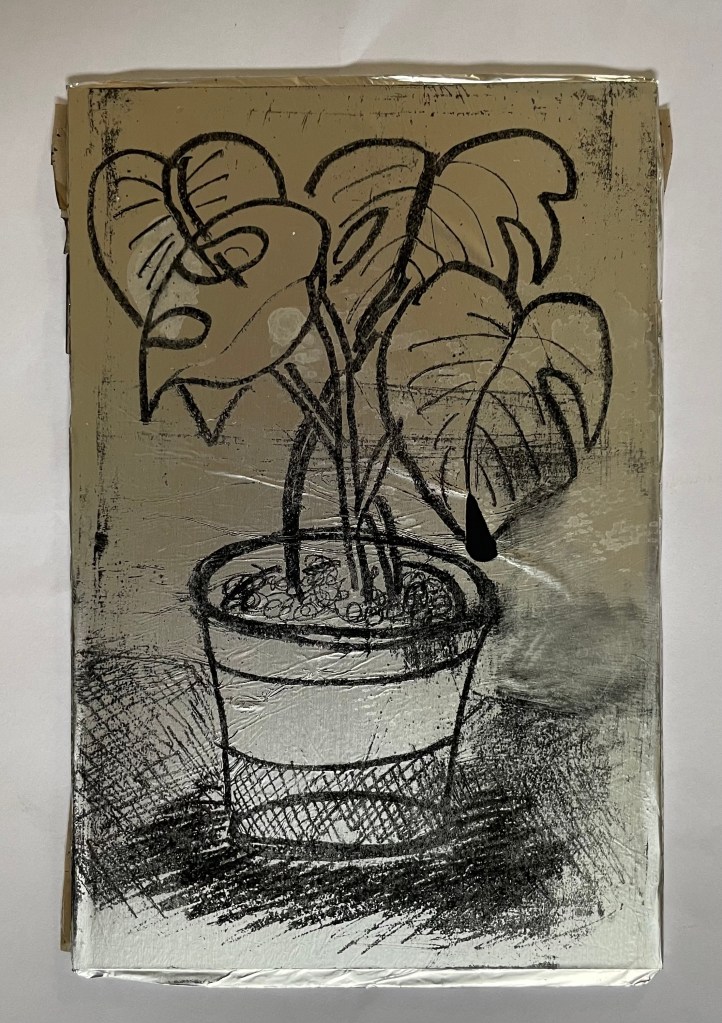

Once I had realised my mistakes I gave it another go. I used a small plexiglass sheet this time, and found some other foil which had a smooth surface. I made a quick, not so good, drawing of the plant in front of me. I used a combination of a chinagraph pencil, basic oil pastel, and a 6B graphite pencil. I did try using a biro, but it ripped a hole in the foil – this was probably because the foil wasn’t very strong. I then poured cola over the top of the plate, rinsed it off, and then rubbed the image away using vegetable oil. Once the plate was dampened with water, I rolled on the ink, re-applying water using a sponge between each ink application. The idea is that the cola contains gum arabic and phosphoric acid which makes the foil which hasn’t been drawn on, hygroscopic. I then used a bamboo baren to transfer the image to a sheet of Hosho paper.

They’re not great, but I’m just happy that I managed to get a defined image at all, bearing in mind my first attempt was such a complete Horlicks.

It felt good trying something new, and what made it particularly enjoyable was the fact that it could be done at home with easily accessible tools and supplies. I will definitely explore it further perhaps after doing some further research so that I can appreciate its full potential. There is a lot of scope for experimentation with different printmakers having different opinions as to the best methodology to adopt: some lightly sand the foil before drawing on it, others use cornflour and maple syrup on the plate; some don’t use a support and just use the foil as a sheet. Maybe the brand of cola has a bearing on whether the process is successful: perhaps I’ll need to have a Pepsi challenge.

Changing Places

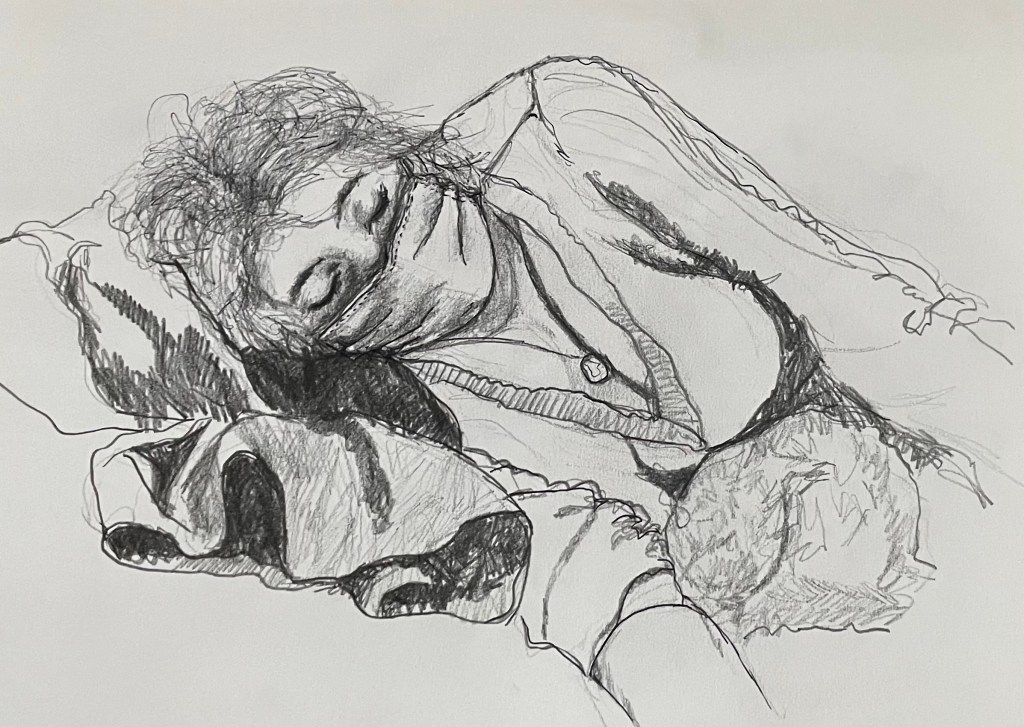

That wasn’t how the last couple of days were supposed to have gone.

My daughter came home from uni just after our session ended on Tuesday with rapid onset tonsillitis. By Wednesday she was in tears. She is one of the bravest and most stoical people I know, so this unsettled me. It’s heartbreaking watching your child suffer in pain. When I was in pain, my mother used to tell me that, if she could, she would swap places with me. I wish I could say the same, but the truth is my daughter is far better equipped to deal with it than me. When it comes to pain, I don’t mind admitting that I’m a wimp. If there are drugs going that will make me feel better, just pump me full of them – that’s what advances in medical science are for, after all.

I don’t care that I didn’t have a ‘natural’ birth, without pain relief; that she came out of the sunroof. I wasn’t ‘too posh to push’ – she wasn’t going anywhere, and at risk of becoming distressed, and would it have mattered if she hadn’t been, anyway? Is a natural birth somehow superior to one with medical intervention? Why are we told, in that patronising way, that we are not the only woman to have ever given birth? I am the only ‘me’ to have given birth.

Whilst I’m doing my best to keep negativity out of my life, some things do just make me angry. I think it is now generally accepted that women are expected to put up with an unnecessary level of pain when it comes to matters of their health, just because they are women. Studies have shown that women experience pain more intensely, and for more of the time than men. However, they are less likely to have their pain scores recorded, or to be prescribed pain relief than men. Apparently, this is based on the misguided notion that women are more emotional, which means that they may exaggerate the pain they are feeling – after all, ‘hysteria’ comes from the Greek word hystera, which means uterus. Really? There is now a term for this way of thinking: medical misogyny.

It reminds me of a comment made by a male healthcare professional whilst discussing pain relief during the discharge process after an exploratory procedure, which had been initially attempted without sedation. Some women can ‘tolerate’ the ‘discomfort’. I wasn’t putting up with the intense pain. Did I feel like a failure, that I’d somehow let myself and womanhood down; that I should have been able to ‘tolerate’ the ‘discomfort’ like all those women who had gone before? Initially, yes, and it is very intimidating to be in a situation where you are surrounded by healthcare professionals, both men and women, where you feel that you have lost agency over what is being done to your body. Did I look in their eyes for judgement, particularly in the women’s, whilst I dressed, gathered my things and left? Yes. But the word ‘no’ is empowering, and so it was sedation for me. Anyway, getting back on point, I think I made some quip as to knowing what pain feels like, being a woman. He must have interpreted that comment as alluding to a badge of honour as to the amount of pain women can tolerate, as he replied, something along the lines of: “Women can’t have it both ways”.

Anyway, I’ve managed to make it all about me again; that wasn’t how this post was supposed to have gone. After several trips to, and many hours spent in A&E, pain relief, antibiotics, fluids, steroids, and a bit of an exploration up her nose and down her throat with a camera, she’s thankfully on the mend with plans to whip the little troublemakers out in due course.

Arty-farty

In the hope of finding some inspiration, I sorted out my art bookcase and came across the exhibition handout to the Michael Craig-Martin exhibition at the Royal Academy. This quote caught my attention:

I dislike jargon intensely and cannot stand people who think that complex ideas need to be expressed in a way that is obscure or rarified… The great minds whom I have admired … are precise and economic in their use of simple language.”

Michael Craig- Martin, “On Being An Artist”

I have to agree with him. I’m very much an advocate of the Plain English campaign. Maybe it’s because I don’t have the necessary range of vocabulary to achieve such verbal smoke and mirrors, or the attention span.

Clarity of language is what made reading Will Gompertz’s ‘Think Like An Artist…’ such a breath of fresh air. He cuts through all the jargon and makes his points in such a way that someone who doesn’t have an ounce of art knowledge would be able to understand and appreciate them.

As Craig-Martin says, it’s not about having very complex ideas: ideas which challenge are good but, if we want art to be accessible to all, why use convoluted and, frankly, nonsensical language to explain and critique it? Is it to maintain an air of mystery, of intellectual superiority? And who is responsible? The artists, the critics, the galleries or curators, or all of them?

Thinking back to our first sessions when we introduced ourselves and our work, I can’t think of a single instance when I didn’t understand the ideas being expressed. There was just authenticity.

This year’s Summer Exhibition is dedicated to art’s capacity to forge dialogues but, how can art ever hope to change things if people just don’t get it? It goes back to the idea of ‘connection’ in my previous post: without a connection, however small, there can’t be engagement, and without engagement there can’t be a dialogue.

When I started this course a friend asked me whether I was going to become all arty-farty. I said I hope not but, if I ever come across that way, she should give me good slap!

It Doesn’t Mean We’re In A Relationship

January has come around again, and I have bought my entry to this year’s RA Summer Exhibition. Will 2025 be my year? Or will I fall at the first hurdle, yet again? The theme for this year’s exhibition is ‘Dialogues’.

When I read this, two other words spring to mind: ‘connection’ and ‘relationship’.

Definitions:

Connection: a relationship in which a person or thing is linked or associated with something else.

Relationship: the way in which two people or things are connected; the state of being connected

Dialogue: a conversation between two or more people; an exchange of ideas and opinions on a particular subject; a process by which people with different perspectives seek understanding.

In the above definitions ‘connection’ and ‘relationship’ seem to be interchangeable. Personally, I think it is possible to have a connection without having a relationship. To me, a connection is an initial link based on shared interests, experiences, understanding and values, whereas a relationship is a sustained connection over a period of time.

I would suggest the following:

- for there to be a dialogue, there at least has to be a connection.

- it is possible to have a connection and a dialogue without having a relationship.

- it is necessary for there to be a connection and a dialogue for there to be a relationship, and to maintain that relationship requires actively nurturing the initial connection, or repeating it, through consistent dialogue, shared experiences and commitment over a period of time.

- it is possible to retain a connection and a dialogue despite the ending of a relationship.

When my daughter comes home from uni she likes to visit her favourite local eatery, the kebab van parked up in a lay-by frequented by lorry drivers. Every time she goes she makes a connection with the owner; they talk; they don’t know each other’s names but he knows, and remembers, where she goes to uni, what she’s studying, that she works at the local Sainsbury’s in the holidays, and how she likes not only her kebab but how we all like ours; my husband, as it comes, me with a little meat and lots of salad, and both garlic and chilli sauce. One might say that they have a relationship.

So, where does all this take me?

To disconnection. We seem to be living in a world in which we are increasingly becoming disconnected, in the sense that we have less meaningful interactions, and consequently we are limiting the opportunity for dialogue and relationships with ourselves, each other and the world around us.

Connections can be made quite easily, for example, on social networking sites, but does that allow for meaningful communication? Does a post followed by a like or a comment constitute dialogue? In fact, by their very nature of facilitating lifestyle curation, social networking sites can cause users to feel disconnected.

One might take the view that dialogue is something more than a mere exchange of words; it involves active listening, empathy, picking up on visual cues, making eye contact, challenging assumptions to create a sense of stronger connection and understanding, the latter being a form of Socratic Dialogue; a continual process of inquiry to deepen understanding. You don’t have the opportunity to exploit these to their fullest when communicating by text, speaking on the phone or on Zoom.

People have even stopped sending the one thing that keeps us connected, particularly to those that are not in our daily lives: Christmas cards. The trend is now to make a donation to charity, apparently. I send Christmas cards every year with the best intentions of reconnecting and furthering some old relationships which have been neglected. If I don’t manage to follow up, at least they’ll send me a change of address if they move, so I can give it another go in the future.

Some of it is a legacy of Covid: it’s easier to deliver university lectures online, to have doctors’ appointments online, to work from home. Whilst I agree that there should be a good work/life balance, not going into a workplace at all and not being able to interact face to face with colleagues, and have water cooler conversations, can’t be a good thing, particularly for young people just starting out in their working lives. The workplace is somewhere to meet friends, or even partners. You can’t really go out for a drink after work, if you’re working from home.

This is a low residency course: we meet weekly on Zoom and communicate with each other on our WhatsApp group. We had an initial connection – our passion for creativity. After the first term we have a deeper connection, and possibly even a relationship in the sense that our connection is fundamentally anchored in a mutual understanding of trust between us. That relationship will deepen further when we meet in person.

I’m not sure where I’m going to go with all of this. Possibly nowhere.

Entries have to be submitted by 11 February, so the next four weeks are going to be very busy with this and my study statement. I’m sort of regretting doing it now: I think that I just wanted to shock myself into doing something. I’m trying not to panic – if I don’t manage it, then that’s fine – I could always submit something I’ve already done, but, if I can, I would prefer to go through the process from scratch.

A Way of Working

As ever, I’m conscious that time is ticking by. Whilst the study statement will be useful to focus what’s buzzing around in my head, moving forward I need to develop a more concentrated and sustainable way of working in order to ensure that I get the most out of the next 5 terms.

Up until now I’ve been all over the place, immersing myself in art, books, programmes, aimlessly ‘doodling’, without any direction, just exposing myself to everything I can and seeing what might stick. Jumping from one thing to another. This process has given me lots of ideas. It’s not too difficult to have ideas – the difficulty is having good ideas and then developing them into a piece of work. I’m feeling that at the moment I’m talking the talk, but not walking the walk.

I lack self-discipline; I get easily distracted; I get bored; I often don’t finish things; sometimes I wake up and know that the day is not going to work for me, and it’s a case of just getting through it; tomorrow’s always another day; I have no routine. I need to establish a routine, if I can, one that allows me to fulfil my everyday responsibilities but which dedicates time to developing creativity. I have no idea how much time I have spent so far on this course. So, moving forward I’m going to record how long I spend doing what. Just roughly, not down to the minute. I’ve had to do this previously – it’s soul destroying having to account for your existence – but the reason for doing it now is to give me a better understanding of how I work, what works for me, whether I’m doing enough and how I need to plan for the future.

Thirty hours a week is a long time, I’ve realised. So, that’s blog 20 mins…