One of my favourite actresses, Lesley Manville, was on Desert Island Discs a few weeks ago. On her divorce from one of my favourite actors, Gary Oldman, who left her a few months after she had given birth to their son, she said:

“I thought we’d be together forever and have a big family. But maybe if that had happened, maybe, I wouldn’t have had the career I have now. I think I’d have given up a lot for a good long marriage, but the price would have been something – I don’t know what.”

This reminded me of ‘The Cost of Living’ by Deborah Levy, in which Levy refers to the relationship between the French philosopher and writer, Simone de Beauvoir, and the American writer, Nelson Algren.

“Algren had written to her when he feared their transatlantic love affair was ending, to tell her the truth about the things he wanted: ‘a place of my own to live in, with a woman of my own and perhaps a child of my own. There’s nothing extraordinary about wanting such things.’

No, there is nothing extraordinary about all those nice things. Except she knew it would cost her more than it would cost him. In the end she decided she couldn’t afford it.”

‘The Cost of Living’ was my choice of inspirational text for our last session.

After listening to the actress, Billie Piper, speaking about it, coincidentally on Desert Island Discs, I thought I would give it a go. I have re-read it many times since, and gifted copies to friends at every opportunity.

Deborah Levy is South African by birth; her father was a political activist who had been imprisoned during Apartheid. The family subsequently relocated to England when she was nine years old.

It’s the second book in a series of three living autobiographies. It covers the period in her life when her marriage fell into difficulties, although her career was on the up having been shortlisted for the Booker Prize. She decided that her marriage was a boat to which she didn’t want to swim back, and so she and her husband divorced. Her family home life no longer fulfilled her need to create, and so it was slowly dismantled.

“We sold the family house. This action of dismantling and packing up a long life lived together seemed to flip time into a weird shape; a flashback to leaving South Africa, the country of my birth, when I was nine years old and a flash-forward to an unknown life I was yet to live at fifty. I was unmaking the home that I’d spent much of my life’s energy creating.

To strip the wallpaper off the fairy tale of The Family House in which the comfort and happiness of men and children have been the priority is to find behind it an unthanked, unloved, neglected, exhausted woman. It requires skill, time, dedication and empathy to create a home that everyone enjoys and that functions well. Above all else, it is an act of immense generosity to be the architect of everyone else’s well-being… To not feel at home in her family home is the beginning of the bigger story of society and its female discontents. If she is not too defeated by the societal story she has enacted with hope, pride, happiness, ambivalence and rage, she will change the story… To unmake a family home is like breaking a clock. So much time has passed through all the dimensions of that home. Apparently, a fox can hear a clock ticking from forty yards away. There was a clock on the kitchen wall of our family home, less than forty yards from the garden. The foxes must have heard it ticking for over a decade. It was now all packed up, lying face down in a box.”

There was a cost to this freedom; this way of living. She moves into a small sixth floor flat at the top of a hill in North London with her daughters and has to teach, and write pieces which she wouldn’t ordinarily choose to, in order to earn a living. She finds that she can’t write in the flat: she needs her own space, so she rents her friend’s garden shed in which she wrote this book and two others.

“It was calm and silent and dark in my shed. I had let go of the life I had planned and was probably out of my depth every day. It’s hard to write and be open and let things in when life is tough, but to keep everything out means there is nothing to work with.”

The book also deals with the death of her mother from cancer. This resonated with me profoundly when I re-read the book after the death of my own mother. There is a moving account of Levy having a meltdown in a local newsagents which had run out of the ice lollies which had been keeping her mother going, as well as her subsequent apology to the three Turkish brothers who owned it.

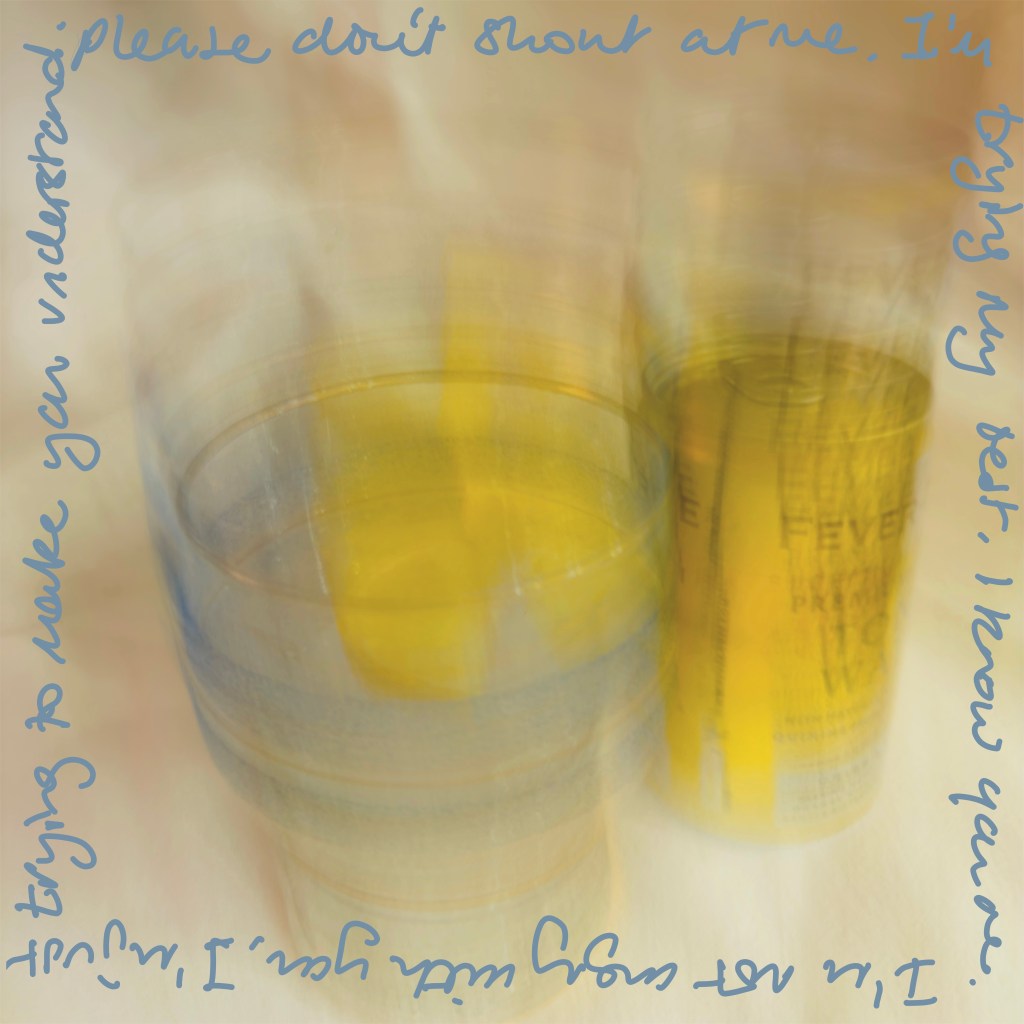

Another poignant moment is when she reflects on a postcard received from her mother:

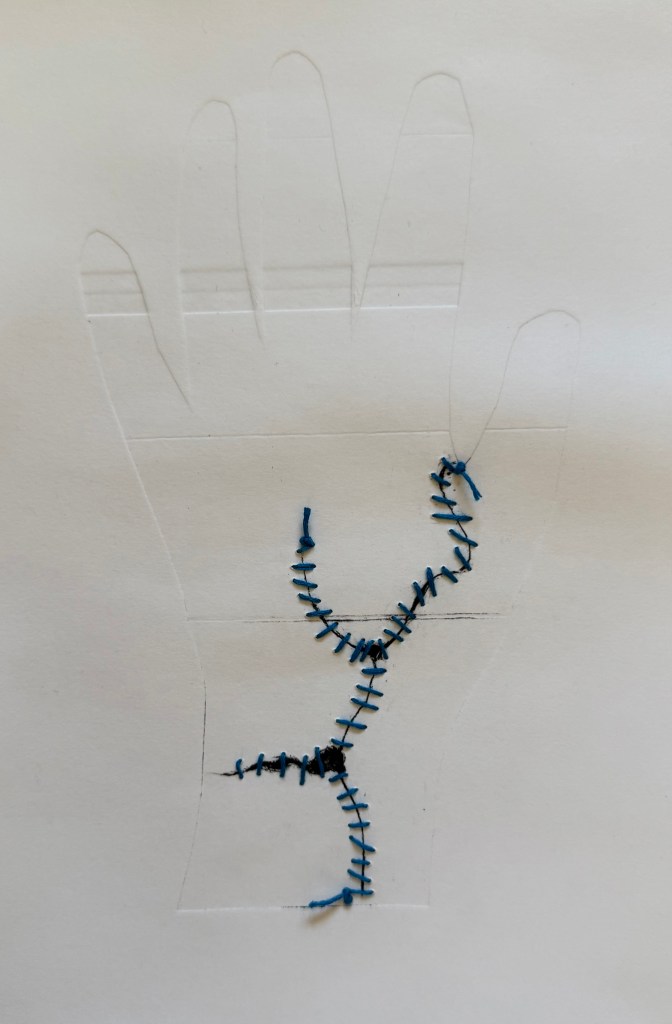

“Love did find its way through the on and off war between myself and my mother. The poet Audre Lorde said it best: ‘I am a reflection of my mother’s secret poetry as well as of her hidden angers.’… My mother had made a biro’d X on the front of the postcard and written’ X is where I am’… It is this X that touches me most now, her hand holding the biro, pressing it into the postcard, marking where she is so that I can find her.”

She goes on to say:

“I lost all sense of geographical direction for a few weeks after my mother’s death. I was disorientated, as if some sort of internal navigation system was drifting… It was she who had raised her children and most childhood memories were twinned with her presence on earth. She was my primal satnav, but now the screen had gone blank.”

I love her way of writing: she can create an impactful image with a few words. Whilst on Eurostar to Paris, she is talking to a teenager sitting next to her, who is using a laptop to learn French, when a man gets on the train and asks the teenager to make space on the table.

” She moved it to her lap. This was a small rearrangement of space, but its outcome meant she had entirely removed herself from the table to make space for his newspaper, sandwich and apple.”

When she is asked to provide a list of the minor and major characters in one of her novels for film execs looking to option it, Levy considers the minor and major characters in her own life.

“If I ever felt free enough to write my life as I felt it, would the point be to feel more real? What was it that I was reaching for? Not for more reality, that was for sure. I certainly did not want to write the major female character that has always been written for Her. I was more interested in a major unwritten female character.”

And that is what I take away from this book, what inspires me: I should be the major character in my own story. It is for this reason that I am on this course, that I am making a change and adopting a new way of living.

This struck a chord with Dalal, who has been thinking a lot recently about the possibility of marriage and family, but is concerned how this might fit in with her need to be an artist. Alex had already established herself as an artist by the time she married and had a family, so her artistic practice had already marked out its boundaries. Pritish is not thinking long-term: his main concern at present is to concentrate on his artistic practice.

I was fascinated to hear about what inspires everyone else. Pritish is inspired by London, in particular, he likes the anonymity it provides and he referenced the photographer, John Deakin; Dalal is inspired by Kerouac’s ‘Satori in Paris’, Murakami’s ‘South of the Border, West of the Sun’ and Muayad H Hussain’s thesis on Khalifa Qattan and circulism; and Rachel Whitehead’s Turner Prize winning House (1993) inspires Alex, a sculpture formed from a concrete cast of the inside of a house condemned for destruction – something made out of nothing containing the past life of the house and its inhabitants, without utility but fascinating.

Now that I have cast myself as the main character in my story, how do I play her?