During my tutorial Jonathan mentioned carbon paper.

It brings back memories of a time when it was the only way to make copies, of secretaries putting a sheet between the top and bottom copies when they typed. Those were the days when the most technologically advanced piece of equipment in the office was a fax machine, which would regularly spew out reams of documents on thin, shiny paper, the print fading away to nothingness over time, thus requiring photocopies to be made, just like some present day shop receipts, so I’ve discovered.

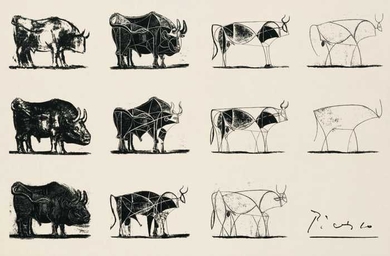

So what to do with it? Recently, I have been reading about map-making and the act of mapping, considering the difference between the two. Contemporary cartographic theorists consider the process of mapping to be of paramount of importance, the creation of the artifact of the map being just one step in the process. In particular, psychogeographic mapping seeks to represent how individuals feel about the place they are in, a process in which subjective experience is prioritised over factual accuracy. Artist, Christian Nold, who uses a bio-mapping device to record individuals’ changes in emotional state, creates emotional maps of places, and one I’m particularly interested in is Brentford Biopsy because I used to live next door in Chiswick before I moved out of London. The project was undertaken in 2008 before areas of Brentford were redeveloped, and it’s really interesting to see how people felt about the area: it reveals so much more information than you would get by simply looking at a map: a map details the historic buildings and the riverside, but not how people respond to them, their view as to how they should be dealt with in future development, and how it actually feels to be there.

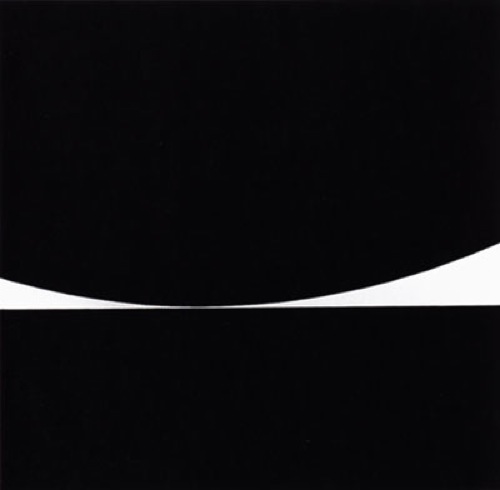

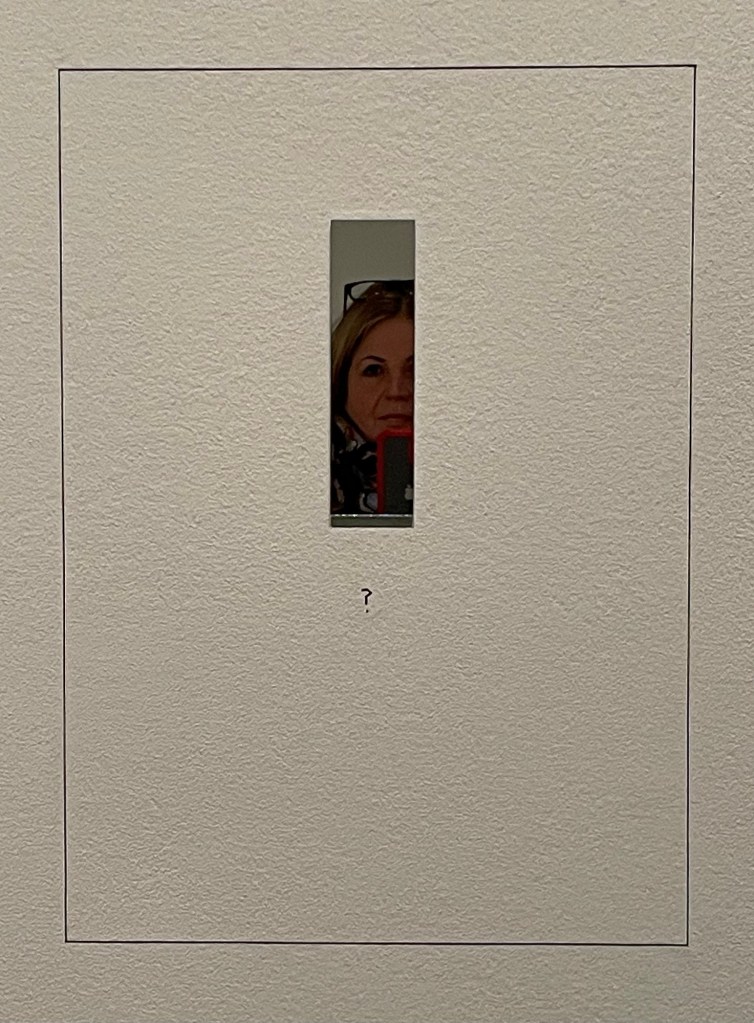

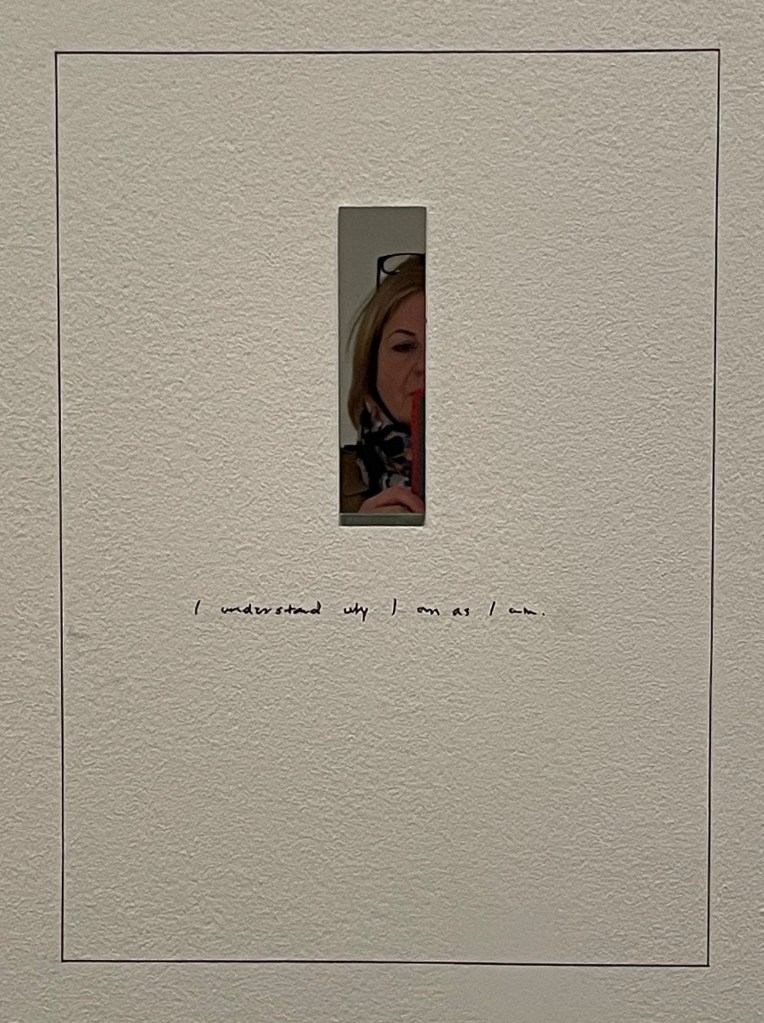

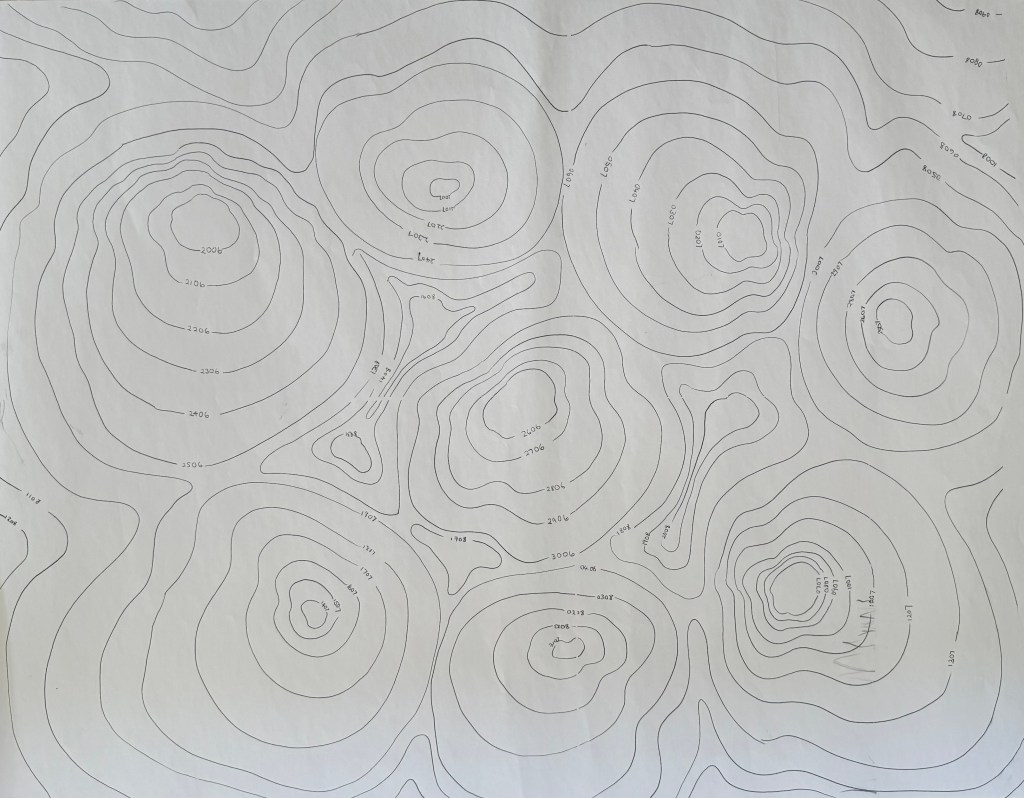

So, I’ve decided to embark on some emotional mapping of my own, not in relation to a sense of place (that may come later when I revisit my grandmother’s village) but of my day to day life. The bonus is that it means that I have to make a line everyday which will hopefully lead me to doing other making. I have drawn the contour lines using carbon paper (I‘m currently thinking that they may be too dark and overpowering, but we’ll see how it goes; it’s an experiment after all) and each one relates to an individual day.

I’ve already started, and it should take me up to the 12th of August. I’ve had to invoke some rules. There are three colours which represent three emotional states which I assess at the end of the day; green represents a neutral emotional state, orange positive and blue negative. Obviously within the generalised emotional states is a whole range of different specific emotions, but I decided just to keep it simple. Each line starts from the contour of the day in question and ends by going off the sheet otherwise it may be associated with more than one day. I draw each line for no longer than two minutes. I had thought about allowing myself however long I felt I needed and varying the intensity of the line depending on how I felt, but decided that would over-complicate things. The map will give an indication of how often I was in each emotional state over a period of time. I’m now thinking that I should have had another map on the go at the same time; not just to depict frequency but also depth of emotion. Maybe next time, if this works out.

I also found some watercolour paper which I had used for an unsuccessful cyanotype and experimented with it. I like the intensity of the colour against the blue background, and the way the coloured in areas look like countries on a map of the world.

The groupings of colours also remind me in a way of the Art Emotions Map which has been produced by Google Arts & Culture and the University of California, Berkeley, which I’ve spent a bit of time exploring and which reminds me of one of our Miro boards. My husband suggested that I could do something similar relating to life experiences, with getting married to him falling within ‘Wonder & Awe’. Oh, he does have a sense of humour!