Almost 20 years old, a bit dated in parts, but still relevant and highly entertaining.

Tag Creativity

Back To Life, Back To Reality

It’s been a blast of a week, with the Interim Show and then the Low Residency. Spending time with like-minded people in an environment of creativity, away from the humdrum of everyday life. And now I’m home, and struggling to get back into the swing of things. I haven’t posted on here for almost a fortnight, which is unusual for me. There is so much to think about and process. I’m not sure where to begin.

In the meantime, I’ve been trying to get on with tasks which don’t require much thought. Today I took the dogs for a walk in some woods which I haven’t been to for a while. It’s predominantly a beech wood. I love beech trees, even when they are leafless. It won’t be long until the bluebells are out and most of the floor of the wood is carpeted in blue, or is it purple? In the meantime, the primroses make me smile. A gentle reminder that time is passing. Maybe my motivation will return tomorrow…

It’s All Part Of The Process

I’ve been doing quite a bit of thinking this week.

The first time, as a result of our weekly session, unprofessional v professional. We considered all that is implicit in the terms professional and unprofessional, and then read and discussed an article ‘How to be an Unprofessional Artist’ by Andrew Berardini, 23 March 2016, MOMUS.

I came away from the session feeling confused, and no longer having a clear sense of direction. My aims in my Study Statement are designed to help me fulfil my aspiration of becoming a practising professional artist. I’m now questioning what I even mean when I use the term ‘professional’. If it means losing creative autonomy, losing the love of creating because it has become an expectation or much worse, a chore; having to repeatedly make things because they are popular or asked for, then, no, I don’t think that’s what I want. But what is the alternative, just to carry on as I am now, making art for me and leave it at that – be a hobbyist like my mother said; be an amateur? I don’t think that’s what I want either. That’s not why I’m here.

Maybe when I get there, if I ever do, the answer will become clear. Perhaps the best course of action is to aspire to be a practising artist for the time being, making more time for creating. There’s no point trying to run before I can even walk.

I then spent some time reflecting on the cyanotypes I made, and all the possible further paths that I could go down. I started thinking about processes and re-processing. How you can take a painting, for example, take a photo of it, digitally alter that photo, incorporate other elements, say, by way of collage, print it out, print on top of it, paint on it, photograph it, keep changing it, keep re-processing it.

It then occurred to me that I’m just one big walking process made up innumerable smaller processes – breathing, talking, thinking, digesting, and on and on. Not just that, but that life is a process with all its constituent processes. Growing, having children, loving, caring, grieving, healing, dying are all processes by which we are, ourselves, processed.

So, I think that I’ve reached a point where I’m thinking about the reprocessing of art and the reprocessing of me. It’s probably because I’ve been thinking a lot about process recently, writing the word goodness knows how many times in Doing Lines, and reading ‘Ultra-Processed People’ by Chris van Tulleken. But it does occur to me that I have led most of my life too focused on the product, and not really living in the process.

Something for me to think about.

Figuring It Out

I’ve started back at my weekly art class after the Christmas break, and over the last two sessions we have been looking at figures, in particular, figures in an environment. I’m not very good at depicting humans (or any animate subject for that matter), so this was a bit of a challenge.

We had to work from images which we had sourced: I took my nieces ice-skating at Christmas, which was really entertaining to watch. There were the confident, well-practised skaters who came equipped with their own boots; the ‘I’m-competent-but every-now-and-then-lose-my-balance-and-windmill-my-arms-brigade; and then the rest – hopelessly clutching the side, or each other, for dear life, inching their way round. There was a whole range of shapes, gestures and weights, in the sense of where in the body the weight is being distributed, and there was a lot of tension.

We started by sketching out the composition.

I used a combination of photos and video stills from my phone – I could have been more organised because I lost track of which figure was on which photo, which wasted quite a bit of time. Next time I work from numerous image sources I will organise them so that they are more accessible and easier to switch between.

I then applied a ground to the support (I used oil paper as opposed to a canvas, as I wasn’t sure how it was going to go). As it was a painting of ice-skaters, I chose burnt umber thinned down with Sansador as my ground, as it’s the blue equivalent of the earth colours. I then drew in the figures using a rigger brush and thinned paint – I found the techniques covered by Chris Koning’s workshop of gestural drawing (‘Perception of the Whole’) to be really helpful in trying to get some dynamism in the portrayal of the figures. I also changed the composition from the pencil sketch to bring forward the pair of skaters on the left and to give the skater next to the pair some extra space into which he could move. I also packed some more figures in, including my favourites, the couple in the centre – the man skating alongside and watching his partner who is leaning forward – and the girl behind them.

The next step was to block in the background. I decided that I didn’t want to put the figures in the specific setting of an ice rink, so I left out the details of the roof and sides which were included in the original sketch. This gives a feeling of more space.

I used a thinned down mixture of titanium white, ultramarine blue and burnt umber to create a grey/blue and then scratched into it with the end of the paintbrush to create skate marks.

I then started blocking in some colour using thinned paint. I liked the fact that the burnt umber drawing was still visible and decided to try and retain as much of it as possible. This meant that I would not be able to use much thick paint in subsequent layers, and so the painting will retain a sketch-like quality. The purpose of the exercise was to capture the essence of the figures, so there will be very little detail in the figures and their faces, other than those in the foreground, and even then I will keep these limited.

I regretted having the large figure in the foreground, but he felt necessary to add variation to the height of the figures, and his static quality should hopefully contrast with the sense of movement in some of the other figures.

I carried on adding some more colour and changed the colour of the skater’s hoodie to differentiate him from the figure in the foreground.

I really enjoyed the process of being looser: the multiple visible alterations and the pared back application of paint. I’m not sure that I like the finished piece, probably because of its subject matter – it’s all a bit twee. But that’s my own fault – I hadn’t adequately prepared for the class and so made a rushed decision. Next time we have to work from a preselected source, I will make sure that I prepare properly, so that the subject matter appeals to me as much as possible.

There are areas which really appeal to me; I like the way I have treated the ice and I think that I have managed to capture the sense of movement, the hesitancy and tension in the figures, and the atmosphere. I don’t like the way I’ve painted the faces in the foreground. Whilst the exercise was all about the figures, I don’t think I’ve managed to find a method to render faces in a non-detailed way which does not look childish. I need to work on this.

I was thinking about this painting whilst I was out on a dog walk yesterday. I enjoyed making it, but I’m not that enamoured with the overall result, which made me ask myself whether I need to like the work I make or whether enjoying the process is enough. Also, I like and am attracted to a wide variety of artists working in very different ways. I suspect that I have previously thought that I need to make myself like them and make the sort of work they make because it is something that I like and am drawn to. I’m starting to realise that this isn’t necessarily the case – I just need to be ‘me’.

Generally, the work which I produce at my art class is not something that I would ordinarily choose to do, (which is a good thing) and won’t necessarily be relevant to my field of study in terms of subject matter, but it will provide a useful source of exploration in terms of technique and approach in my art practice. As such it is a valuable resource and a good use of time as well as a commitment which ensures that I create work on a regular basis.

ARTificial Intelligence II

I’ve just been watching ‘Sunday with Laura Kuenssberg’ and one of her guests was Baroness Beeban Kidron, a former film director who was appointed as a crossbench peer. She specialises in protecting children’s rights in the digital world, and is an authority on digital regulation and accountability.

The topic of conversation was Labour’s plan to change copyright law so that tech companies can scrape copyrighted work from the internet to train their generative AI tools free of charge, unless individual creatives decide to opt out. They are proposing what is, in essence, legalised theft.

Labour launched their AI Opportunities Action Plan two weeks ago. They intend that the UK should become a world leader in AI with the amount of computing power under public control being increased 20 times over by 2030. They will achieve this by making huge investments (£14bn provided by tech companies, of course!) in setting up the infrastructure needed to create AI growth zones, a ‘super computer’ as well as huge energy intensive data centres necessary to support it. Clearly this will have a significant environmental impact and is at odds with Labour’s election promise to hit its green target to create a clean power system by the same date of 2030, which some experts think was going to be difficult to meet anyway.

Apparently, this will result in the UK’s economy being boosted by £470bn over the next 10 years. This may well turn out to be Starmer’s figure on the side of the bus. Kidron commented that the small print reveals that the figure was sourced from a tech lobbying group which was paid for Google and which was arrived at by asking generative AI, and which, in any event, reflects the global, not the national, uplift in the economy.

Kidron is a vocal supporter of the option to opt-in rather than putting the onus on the individual creative to contact each of the AI companies, who are using their work, to opt out. In fact, opting-out is something that’s not technically possible to do at the moment. To this end, she has put forward amendments to the Data (Use and Access) Bill which will be debated in the House of Lords this week. She has also previously commented in the press that she can’t think of another situation in which someone who is protected by law must actively wrap it around themselves on an individual basis. I think she makes a good point, and I agree with her view that the solution is to review the copyright laws and make them fit for purpose in an AI age. The creative sector, which includes artists, photographers, musicians, writers, journalists, and anyone else who creates original content, is made up of about 2.4 million people and is hugely important to the country’s economy, generating £126bn. That money should be kept within the economy, and not be siphoned off to Silicon Valley.

Not surprisingly there has been a great deal of backlash from creatives including actors and musicians, such as Kate Bush and Sir Paul McCartney, since Labour announced their plans. As part of the segment, Kuenssberg interviewed McCartney who is very concerned as to the effect this will have, especially on young up and coming artists. He commented that art is not just about the ‘muse’ but is about earning an income which allows the artist to keep on creating. He fears that people will just stop creating because they won’t own what they create, and someone else will profit from it. AI is also a positive thing: he explained that they used it to clean up John Lennon’s voice from a scratchy cassette recording making it sound like he only recorded it yesterday, but he is, nevertheless, concerned by its ability to ‘rip off’ artists. He mentioned that there is a recording of him singing ‘God Only Knows’ by the Beach Boys. He never recorded the track; it was created by AI. He can tell it doesn’t quite sound like him, but a normal bystander wouldn’t be able to tell the difference. In a year’s time, even he won’t be able to tell the difference.

There is a petition which has been signed by over 40,000 creatives, and the Government is undergoing a consultation procedure which you can respond to with your comments online here. The consultation ends on 25th February.

So, what can we do in the meantime?

Short of going offline, which isn’t really an option, there is nothing which will ensure that our work is not used in training generative AI. Just from some cursory research, which incidentally was helpfully summarised by Google’s AI Overview, there is the possibility of using a watermark to protect images either physically (not so good for promoting work) or invisibly embedded in the image, using digital signatures, or a cloaking app such as Glaze, which was developed by the University of Chicago, which confuses the way AI sees your image by altering the pixels, or by using another of their apps, Nightshade, which alters the match between image and descriptive text.

For now, all I can do is to change my privacy settings on my Facebook and Instagram accounts to prevent Meta from being able to use data from my posts to train its own AI tools. I had to fill in a form explaining why I objected to them using the data, and I received email confirmation that they would honour my objection, but who’s to know if they do or not? Apparently, there is a website, Have I Been Trained?, which allows you to search for your work in the most popular AI image dataset, LAION-5B.

What’s possibly just as disturbing is the Government’s plan to allow big tech access to one of the biggest and comprehensive datasets in the world – the NHS. It’s all in one place, we all have an NHS number which gives access to a lifetime’s history of personal and health data. It will be done on an anonymous basis, but with enough data, even experts say it’s easy to re-identify people. No-one’s doubting the incredible possibilities that AI offers in terms of delivering healthcare, but proper safeguards are needed.

Anyway, I asked the WordPress AI to generate a header image based on its own prompt:

“Create a high-resolution, highly detailed image illustrating the theme of digital rights and AI regulation. Feature Baroness Beeban Kidron in a thoughtful pose, surrounded by symbols of creativity such as art supplies, musical instruments, and books. The backdrop should convey a digital landscape, with elements representing technology and copyright, like binary code and padlocks. Use soft, natural light to evoke a sense of seriousness, yet hopefulness. The image should be in a documentary style, capturing the urgency of the conversation about protecting creatives’ rights in the age of AI. Ensure sharp focus to highlight the intricate details in each element.”

Sorry, Jonathan – I will switch my mobile phone off for the rest of the day so I don’t have to recharge the battery, but, in the meantime, do we have much to worry about? It doesn’t even look like Beeban Kidron.

It Doesn’t Mean We’re In A Relationship

January has come around again, and I have bought my entry to this year’s RA Summer Exhibition. Will 2025 be my year? Or will I fall at the first hurdle, yet again? The theme for this year’s exhibition is ‘Dialogues’.

When I read this, two other words spring to mind: ‘connection’ and ‘relationship’.

Definitions:

Connection: a relationship in which a person or thing is linked or associated with something else.

Relationship: the way in which two people or things are connected; the state of being connected

Dialogue: a conversation between two or more people; an exchange of ideas and opinions on a particular subject; a process by which people with different perspectives seek understanding.

In the above definitions ‘connection’ and ‘relationship’ seem to be interchangeable. Personally, I think it is possible to have a connection without having a relationship. To me, a connection is an initial link based on shared interests, experiences, understanding and values, whereas a relationship is a sustained connection over a period of time.

I would suggest the following:

- for there to be a dialogue, there at least has to be a connection.

- it is possible to have a connection and a dialogue without having a relationship.

- it is necessary for there to be a connection and a dialogue for there to be a relationship, and to maintain that relationship requires actively nurturing the initial connection, or repeating it, through consistent dialogue, shared experiences and commitment over a period of time.

- it is possible to retain a connection and a dialogue despite the ending of a relationship.

When my daughter comes home from uni she likes to visit her favourite local eatery, the kebab van parked up in a lay-by frequented by lorry drivers. Every time she goes she makes a connection with the owner; they talk; they don’t know each other’s names but he knows, and remembers, where she goes to uni, what she’s studying, that she works at the local Sainsbury’s in the holidays, and how she likes not only her kebab but how we all like ours; my husband, as it comes, me with a little meat and lots of salad, and both garlic and chilli sauce. One might say that they have a relationship.

So, where does all this take me?

To disconnection. We seem to be living in a world in which we are increasingly becoming disconnected, in the sense that we have less meaningful interactions, and consequently we are limiting the opportunity for dialogue and relationships with ourselves, each other and the world around us.

Connections can be made quite easily, for example, on social networking sites, but does that allow for meaningful communication? Does a post followed by a like or a comment constitute dialogue? In fact, by their very nature of facilitating lifestyle curation, social networking sites can cause users to feel disconnected.

One might take the view that dialogue is something more than a mere exchange of words; it involves active listening, empathy, picking up on visual cues, making eye contact, challenging assumptions to create a sense of stronger connection and understanding, the latter being a form of Socratic Dialogue; a continual process of inquiry to deepen understanding. You don’t have the opportunity to exploit these to their fullest when communicating by text, speaking on the phone or on Zoom.

People have even stopped sending the one thing that keeps us connected, particularly to those that are not in our daily lives: Christmas cards. The trend is now to make a donation to charity, apparently. I send Christmas cards every year with the best intentions of reconnecting and furthering some old relationships which have been neglected. If I don’t manage to follow up, at least they’ll send me a change of address if they move, so I can give it another go in the future.

Some of it is a legacy of Covid: it’s easier to deliver university lectures online, to have doctors’ appointments online, to work from home. Whilst I agree that there should be a good work/life balance, not going into a workplace at all and not being able to interact face to face with colleagues, and have water cooler conversations, can’t be a good thing, particularly for young people just starting out in their working lives. The workplace is somewhere to meet friends, or even partners. You can’t really go out for a drink after work, if you’re working from home.

This is a low residency course: we meet weekly on Zoom and communicate with each other on our WhatsApp group. We had an initial connection – our passion for creativity. After the first term we have a deeper connection, and possibly even a relationship in the sense that our connection is fundamentally anchored in a mutual understanding of trust between us. That relationship will deepen further when we meet in person.

I’m not sure where I’m going to go with all of this. Possibly nowhere.

Entries have to be submitted by 11 February, so the next four weeks are going to be very busy with this and my study statement. I’m sort of regretting doing it now: I think that I just wanted to shock myself into doing something. I’m trying not to panic – if I don’t manage it, then that’s fine – I could always submit something I’ve already done, but, if I can, I would prefer to go through the process from scratch.

A Way of Working

As ever, I’m conscious that time is ticking by. Whilst the study statement will be useful to focus what’s buzzing around in my head, moving forward I need to develop a more concentrated and sustainable way of working in order to ensure that I get the most out of the next 5 terms.

Up until now I’ve been all over the place, immersing myself in art, books, programmes, aimlessly ‘doodling’, without any direction, just exposing myself to everything I can and seeing what might stick. Jumping from one thing to another. This process has given me lots of ideas. It’s not too difficult to have ideas – the difficulty is having good ideas and then developing them into a piece of work. I’m feeling that at the moment I’m talking the talk, but not walking the walk.

I lack self-discipline; I get easily distracted; I get bored; I often don’t finish things; sometimes I wake up and know that the day is not going to work for me, and it’s a case of just getting through it; tomorrow’s always another day; I have no routine. I need to establish a routine, if I can, one that allows me to fulfil my everyday responsibilities but which dedicates time to developing creativity. I have no idea how much time I have spent so far on this course. So, moving forward I’m going to record how long I spend doing what. Just roughly, not down to the minute. I’ve had to do this previously – it’s soul destroying having to account for your existence – but the reason for doing it now is to give me a better understanding of how I work, what works for me, whether I’m doing enough and how I need to plan for the future.

Thirty hours a week is a long time, I’ve realised. So, that’s blog 20 mins…

Part Two: Think Like An Artist

On the act of creating:

Gompertz reflects on the ability of creatives to think about both the big picture, and the fine detail.

”It requires your mind to constantly go back and forth, one moment concerned with the minutiae, the next stepping away and seeing the broader context… One tiny dab of colour can radically change the appearance of the largest of paintings. Each stroke of the brush is a note struck in a visual concerto; any mistake is as obvious to the viewer as hearing an orchestra member hit a wrong note.”

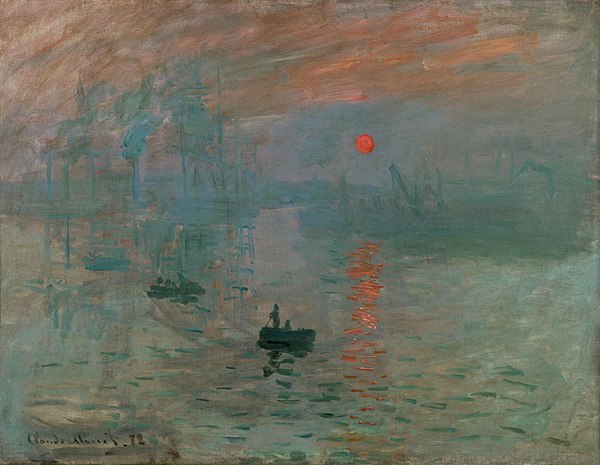

It’s true that the tiniest detail can make a painting: the small detail of the red sun makes this work by Monet.

Sunrise, 1872, Monet (Wikipedia 7 Jan 2025)

Gompertz describes a visit he made to the studio of Belgian artist, Luc Tuymans.

He is intrigued by Tuymans’ work and its ability to make him want to look closer. Tuymans explains that every painting has a point of entry: a small detail that catches your eye and draws you in. He is influenced by other artists who use this trick: Hopper, Van Eyck and Vermeer. In the case of the latter, Gompertz explains that the point of entry for ‘Girl with a Pearl Earring’ might be assumed to be the highlight on the earring but, in fact, conservators uncovered an alternative point of entry: a small dot of pale pink paint in the corner of her mouth, which serves to change the overall reading of the painting.

Detail ‘Girl With a Pearl Earring, 1665, Vermeer

As an aside, to my mind, the point of entry in Monet’s ‘Sunrise’ above is the red sun, going down through the buildings on the right, the reflection on the water, back up to the boat in the foreground, to the boats behind, up to the buildings in the distance, into the sky and following the directional brushstrokes up to the top righthand corner.

Tuymans completes his paintings within the course of a day; he uses the edge of the canvas as his palette which allows him to work quickly, as does his preconceived detailed plan, which can sometimes have begun many months, if not years, before. In fact, Tuymans goes so far as to plan an entire exhibition upfront before he has even started work, from the relationship between each painting, its size, location, the colour of the wall on which it will hang, and so on. His rationale for treating his work as a unit in this way is that to make sense of it, all of the paintings will need to be seen together, and so he increases the chances of there being a major retrospective of his work once he is dead. Now, that’s seeing the bigger picture!

I’m not really sure what I think about this. Planning work in such an extensive and detailed way seems very restrictive to me. Having said that, I would assume that his planning process includes a prolonged period of experimentation before committing to the final piece, which is why he can complete it in a day. He also uses existing images as a basis for his work, which is likely to reduce the number of questions he has to ask himself.

As for the focus on his legacy, I really can’t make up my mind. I suppose it depends on why artists, and in particular, Tuymans, make art. Is it to make the world a better place? Is it to fulfil the need to express themselves? Is it to leave a lasting mark on the world? Is it to make money? Is it because they simply have to? It’s probably a combination of all of these things, with some being of greater significance than others. I just get the feeling in Tuymans’ case that it’s rather contrived, and predominantly about his legacy. I actually wish that I hadn’t read this about him: for me it is a distraction from his work, which is primarily concerned with people, and their relationships with the past.

John Playfair, 2014, Luc Tuymans & John Playfair, 1824, Henry Raeburn (momus.ca 7/1/25)

I’m reminded of Sean Scully. My mother couldn’t stand Sean Scully. In fact, she didn’t rate Picasso either. I remember a conversation I had with her when she phoned me up one morning: she hadn’t been able to get to sleep the night before, so she had got up, made herself a cup of tea and put the TV on. She ended up watching a documentary on Sean Scully. She hadn’t been able to get to sleep after it either, as she had been so incensed by it. Did I know that his paintings, basically just coloured stripes, sold for millions of pounds? I suspect the problem had arisen because the programme makers had juxtaposed some footage of Scully applying some paint to a canvas in a rather sloppy slapdash fashion with footage of one of his paintings being sold at auction. I think it was one of those ‘I could have done that’ moments, but I resisted the urge to give the obvious answer ‘But you haven’t, have you?’, and instead commented that it’s because he is actually a very astute businessman. From what I understand, Scully controls the supply of his art into the art market, retaining a significant number of works himself, thus reducing supply, increasing demand and driving up prices, whilst at the same time ensuring that there is plenty of his work readily available for retrospectives. Basic economics, really.

Song (1985), Sean Scully approx value 2022 £1.6M (sothebys.com 7/1/25)

It all comes down to the uncomfortable relationship between the creation of art and profit, which Gompertz deals with early on in his book, and which I wasn’t planning on covering, but as I seem to have found myself here anyway…

On money:

At it’s very simplest, if you are a professional artist then you need to earn an income from your work to survive. But the relationship between art and money raises so many questions. Is the problem the amount you earn and what you do with it? Which is more worthwhile – the work of a penniless artist slaving away in a garret, or an artist who plays the game and exploits the brand conscious wealthy consumers? Does the need to earn an income compromise or limit an artist’s ability to express themselves authentically? Sophie, in her post reflecting on the first term, refers to the new sense of creative freedom she has experienced, away from the conveyor belt of producing work which would appeal to past and future buyers of her paintings. It is a subject we’ve touched on briefly in our weekly sessions, and it seems a very delicate balance to get right. I think Gompertz probably sums it up best:

“The intellectual and emotional motivation isn’t profit, but it is an essential component. Profit buys freedom. Freedom provides time. And time, for an artist, is the most valuable of commodities.”

In his book, Gompertz explores the issue of artistic entrepreneurism by starting with the artist who didn’t shy away from the subject of money and materialism by making his art all about them: Andy Warhol.

“Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.” Andy Warhol

He then covers the likes of Reubens, an expert salesman, who went off ringing the doorbells of the aristocracy and royalty of Europe whilst his minions worked endlessly in his workshops; Van Gogh and his money man, Theo; and American artist, Theaster Gates, who uses the proceeds of his art to buy and refurbish buildings for use by the community in the South Side of Chicago, where he grew up, thereby regenerating the area and effecting positive social change.

‘Chorus’, 2016, Theaster Gates

I had hoped to have covered much more of the book in this post – it may end up having as many parts as The Godfather! The fact that I have had so much to take note of and comment on, is proof that I am finding it incredibly insightful. I am aware that, at the moment, I’m using this blog for note-making. I have to, otherwise I’ll forget it all. I have lost count of the number of times I’ve read a fact and thought, oh that’s interesting, I must remember that, only for it to disappear again. It infuriates me that I can’t recall facts and statistics at the drop of a hat when having a discussion about something, whilst the other person seems to be able to pluck them out of thin air in support of what they are saying. Or maybe that’s exactly what they are doing – they do say that if you say something with enough confidence people will believe you…

Reflection

I’ve decided to take a leaf out of Sophie’s book and formalise the thoughts I’ve had since we finished our first term.

I don’t think that I have felt more like myself (whoever that might be) than I have over the course of the last 3 months. I can’t pinpoint why exactly; I’ve just felt like ‘me’.

It has been overwhelming (I suspect that I use this word an awful lot) in the sense that I have been totally free to create and, more importantly, to think about creating. I feel as if I am at the start of an important journey – I don’t want to rush into it; I want to take my time and be prepared. I don’t even know where I’m going – there are no limitations – but I know that I will discover something by the end of it.

I think that I have mostly engaged in the preparation side of things rather than the physical manifestation of work, but that’s been the best bit. I’ve been collecting ideas, inspiration, and information. I think about it most of the time. I’ll have a thought and think, yes, I could use that, and then it’s gone. I need to find a workable way of recording my thoughts – I can’t really open a notebook or Notes on my phone whilst driving – maybe I’ll have to call someone (hands free, of course) and get them to record it for me. Funnily enough, I used to do that: if, whilst at home, I thought of something I needed to do at work the next day, I would call my work phone and leave a voicemail. Just writing that has made me think about what voicemails I might leave younger versions of myself at various points in my life. And that is how it’s been, going off on tangents, suddenly striking up a conversation with whoever I’m with, on the thought I’ve just had.

It has also made me feel anxious – I don’t want to miss anything. I have amassed a large pile of books which I ‘need’ to read. I haven’t really tackled the online library resources with any conviction just yet – the thought of it makes my heart race – all that information out there – how can I take it all in?

The preparation of my study statement has come at just the right time. I need to marshall my thoughts and commit them to words, but in the knowledge that it is a living document which can change over time. I’m actually really looking forward to it as it will bring a sense of calm and order. I hope. Who knows, I might be feeling differently come the beginning of February.

Thinking back on the work I have done over the last few months, I think I have become much freer – I’ve been leaving things as being what I would term as ‘unfinished’ and managing not to go back to them. Making them public by putting them on this blog has helped tremendously. I’m now enjoying the process of making much more than I have previously – it was often an ordeal.

I think I have identified areas which I would like to explore in more depth: I have invested in a book on Procreate (it’s not going to beat me) which I’m working my way through, and I have some ideas in my head as to a series of three digital collages on the subject of motherhood which I may or may not develop further. I like the number three: I am one of three; there are three in my immediate family; there are three trees which together form one tree on my favourite walk near my home; and three is the smallest number by which you can seek the input of others and still avoid a deadlock. Having said that, it’s probably not so great for a friendship group.

I would also like to experiment with printing techniques, photography and a previous obsession, cyanotypes. This term I’m determined to book some sessions and get into CSM on a regular basis.

I’m now able to look back at the three monotypes that I made of my mother. I feel that it was the right thing to do. It was something that I always knew I would have to address and it was something that I had to tackle early doors. I think it has helped. I went back to my mother’s house not so long ago and I didn’t feel the usual sinking feeling of dread as I walked through the front door. I was actually able to sit down by myself in silence and remember some of the good times when we all lived there as a family, even when it became dark outside. A small positive step in the right direction.

As finished pieces of work, they are what they are, vehicles by which I transferred debilitating thoughts into another space. Could I have done them differently or executed them better? Yes, obviously, but I don’t look at them that way; it is what they signify and make me feel that matters: despair, confusion, sadness, resentment, helplessness, isolation and fear. I chose monotype because it is, as soon as it is, and there is no way back. It was all about the process, not the result. If I had to make a change I would change their order – I made them in the order of the conversations – they would work better as a series if their order was reversed, with each one making more sense of the one before.

I took my daughter back to uni at the weekend, and she phoned me up earlier, chasing me for some information I was supposed to give her. My husband chipped in that it wasn’t any wonder that I hadn’t got round to it as I seem to spend all my time blogging – well, if I don’t have anything else to show for the next year and a half, at least I’ll have this blog!

Part One: Think Like An Artist

… and Lead a More Creative, Productive Life by Will Gompertz isn’t taking me long to read at all. Gompertz, artistic director at the Barbican, makes some very interesting and thought-provoking observations on what it is to be creative. As I’m galloping through it at such a speed, I thought it best to highlight some parts, as I go along, which I think will either help me in finding my artistic voice, or which reinforce ideas and concepts which we have touched on in the course so far.

On failure:

”When it comes to creativity, failure is as inevitable as it is unavoidable. It is part of the very fabric of making. All artists, regardless of their discipline, aim for perfection…But they know perfection is unobtainable. And therefore they have to accept that everything they produce is doomed to be a failure to some extent…Thomas Edison knew all about the notion of sticking at it…But at no point did he countenance failure: ‘I have not failed 10,000 times,’ he said. ‘I have not failed once. I have succeeded in proving that those 10,000 ways will not work. When I have eliminated the ways that will not work, I will find a way that will work‘…There is plenty of time for wrong turns, for getting lost; for feeling generally hopeless. The crucial thing is to keep going. Artists appear glamorous and blessedly detached, but in reality they are tenacious grafters: they are the proverbial dogs with bones… And while they are out there, worrying away, they often discover a hidden truth about the creative process… Their success is very often down to a Plan B. That is, the thing they originally set out to do has morphed along the way into something different.”

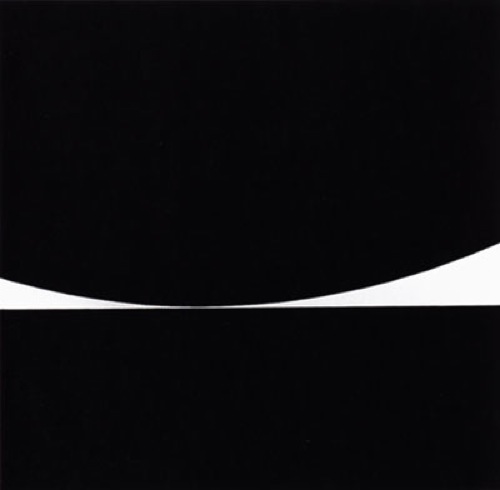

He references several artists who started out in one direction only to find their success through a Plan B, such as Mondrian, Lictenstein and Bridget Riley. In the case of the latter, in the early part of her career Riley was interested in colour theory and the work of the Impressionists, the Pointillism of Seurat, and the composition of Cézanne. It wasn’t working for her; she was directionless and lacked originality, and she was getting older. The ending of a relationship caused her to paint a canvas black, and she took all that she had learnt from her studies of Seurat et al and applied her knowledge in abstract terms. She painted a white horizontal line the lower edge straight, the upper edge forming a curve – it became a painting expressing the dynamism and inequality of relationships, human and spatial.

’Kiss’, 1961, Bridget Riley (Wikiart 4 Jan 2025)

”Bridget Riley had to abandon the one thing she thought most important and appealing about painting – colour – in order to make any real progress. It didn’t mean colour could never feature in her work again, only that at that precise moment in time it was the roadblock… Only when [she] went back to the most basic of basics – a canvas covered in black paint – did she find the necessary clarity to progress. Only then did she discover the most precious and liberating of things: her artistic voice… As long as you stick at what you are doing, constantly going through the cycle of experimentation, assessment and correction, the chances are you will reach the moment when everything falls into place.”

The cycle of experimentation, assessment and correction is at the very essence of this course: Practice-based research.

Gompertz also states that if you call yourself an artist and make art, then you are an artist regardless of where you are in the process, or what skills you still need to learn and develop. I think I find this the hardest to embrace – I still can’t quite think of myself that way. I’ve only just got my head around being a student – in retrospect, it probably wasn’t the best idea to try it out first on the border official at Marrakech airport who looked at me with incredulity and repeated “Student?”. Admittedly, it’s been a lot easier since I discovered all the discounts available!

On ideas:

Gompertz asserts that originality in a completely pure form does not exist; that all ideas are additional links in an existing chain, each link adding to the one before. It is a form of disruption: something to react against and respond to, to build upon. He suggests that Picasso, in the quote attributed to him – good artists copy, great artists steal – is actually describing a process that an artist needs to go through: we learn through copying and imitating, and it is only once we have done this and developed the basic techniques that we can identify opportunities to add our own link to the chain, and to find our own artistic voice. This reminds me of my discussion with Jonathan about Frida Kahlo’s ‘The Two Fridas’, when I questioned whether any work I make which is inspired by it will be original enough: he advised me that Kahlo painted it in the late 1930s and I would be doing my version almost 90 years later expressing my own feelings – following Gompertz’s reasoning, I would, in effect, be adding my own link to her existing link in the chain.

In fact there are numerous creatives who have been quoted as admitting to building on the ideas of others.

” If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” Isaac Newton

“ Creativity is knowing how to hide your sources” Einstein

”We have always been shameless about stealing great ideas”. Steve Jobs

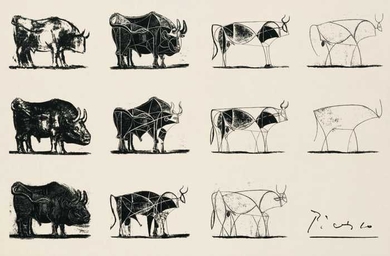

The young Picasso produced work which imitated the likes of Goya, Velázquez and El Greco, and later the Impressionists and Post Impressionists. It was only when his friend, Casagemas, died that he found his own artistic voice in his Blue Period; the blocks of colour, bold lines and expressive manner, which he had learnt from all those artists he had imitated, still influenced him, he just put his own twist on it. He took their ideas and filtered them through his own personality and experience, and used his instincts to simplify and reduce them into his original thought, into new and unique connections. Being creative isn’t always about adding to something; it can be at its most original when taking something away. This is demonstrated perfectly by Picasso’s bull lithographs, which took him a month to complete.

‘Le Taureau‘, 1945/46 (Wikipedia, 5 January 2025)

”There is no such thing as a wholly original idea. But there is such a thing as unique combinations.” Gompertz