It was a colourful day yesterday.

It started with a bracing dog walk, first thing. It was the best start to the day.

Then a train ride to London to visit the Michael Craig-Martin exhibition at the Royal Academy before it closes in a little over a week. I have to say that going into a gallery has the same effect on me as going into a church – a sense of wonderment and contemplation comes over me: people even speak in hushed tones.

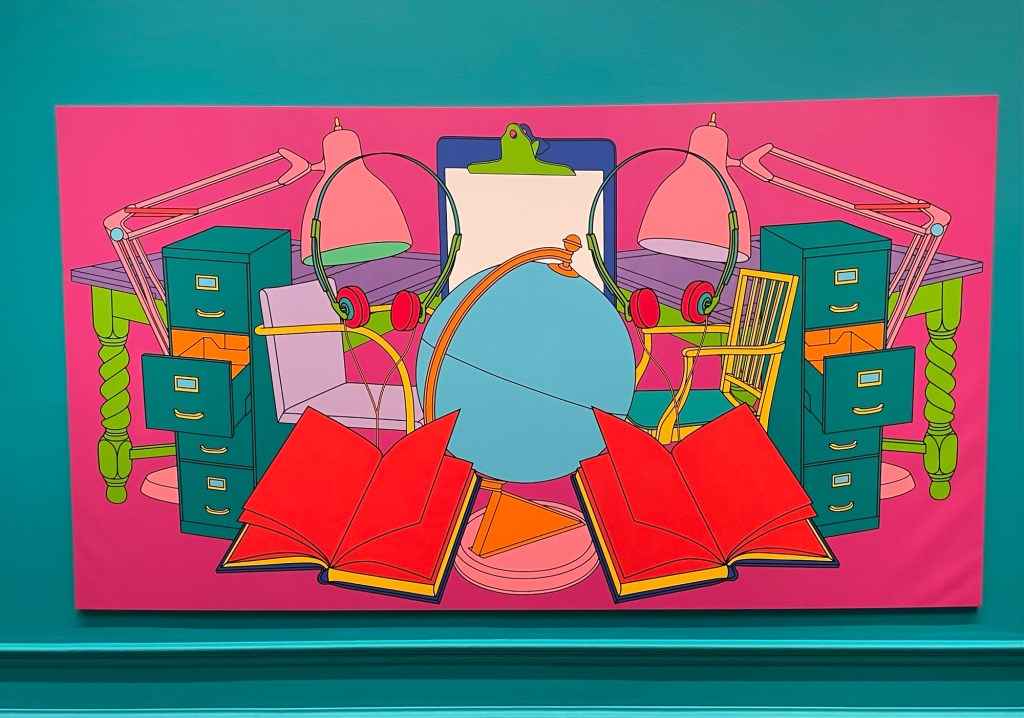

It was joyously colourful, but for me, that was just about it. I was left wondering to myself, if it wasn’t for the painted walls and the sheer scale of some of the works, would they still have been so impactful? If they had been A3 in size and hanging on a bare white wall, would I still have experienced chromatic overload? I used to be attracted to the graphic simplicity of his work, elevating everyday objects to something out of the ordinary, but I’m sad to say that I don’t think it does it for me anymore. I’ve changed. If anything, I was more intrigued by his earlier conceptual work.

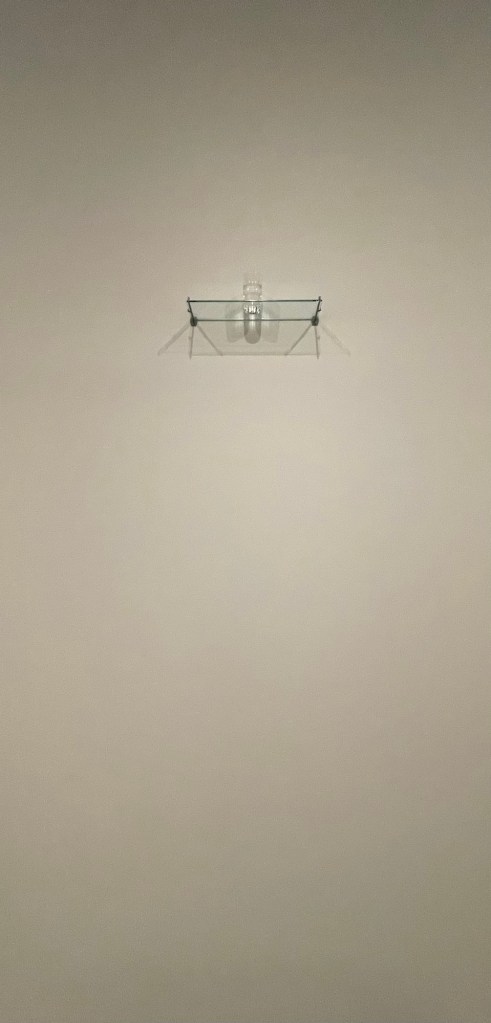

The Oak Tree (1974) is a small glass filled with water to a specific level and mounted on a wall at a specific height of 253cm. It is accompanied by the text of a conversation in which Craig-Martin explains how he has changed the glass of water into an oak tree without changing the physical form of the glass – I don’t know whether it was meant to be amusing, but I certainly had a titter. In a short film for the RA, which I watched when I got back home, he explains that he was trying to find something that constituted the essence of art, in that art is based on the notion of transformation, and the most extreme proposition for transformation would be to have no transformation at all. Others have alluded to his Catholic upbringing and have suggested that it is to do with transubstantiation. I also read that it was seized by Australian customs officials on its way to an exhibition in the 1970s on the basis that it was illegal to import plants into Australia!

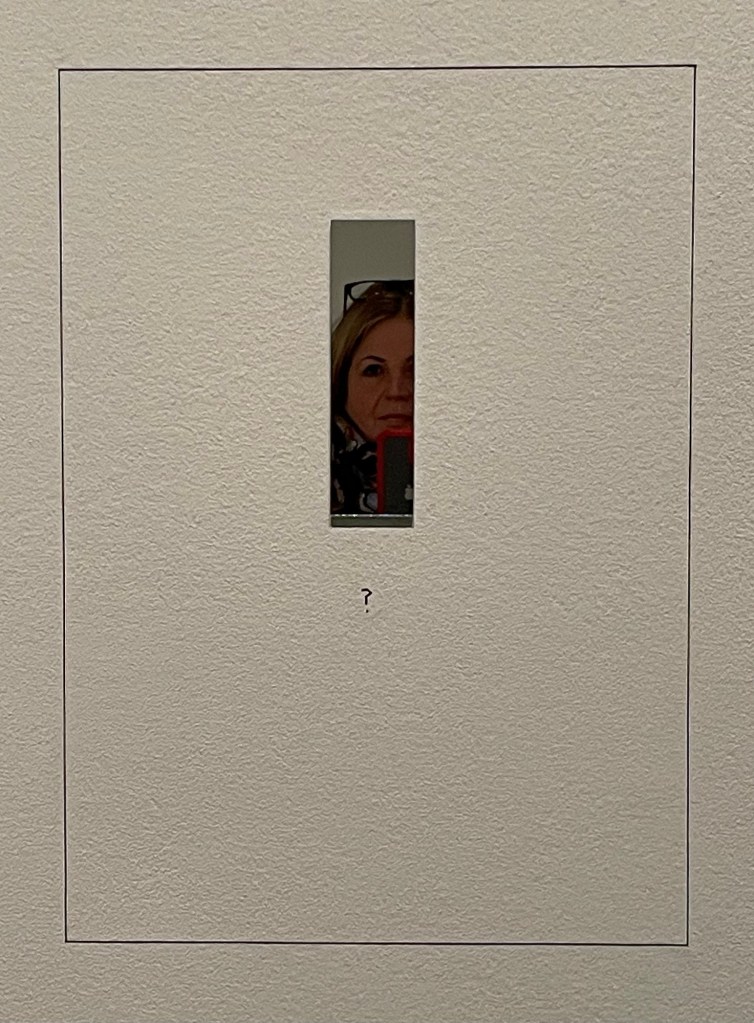

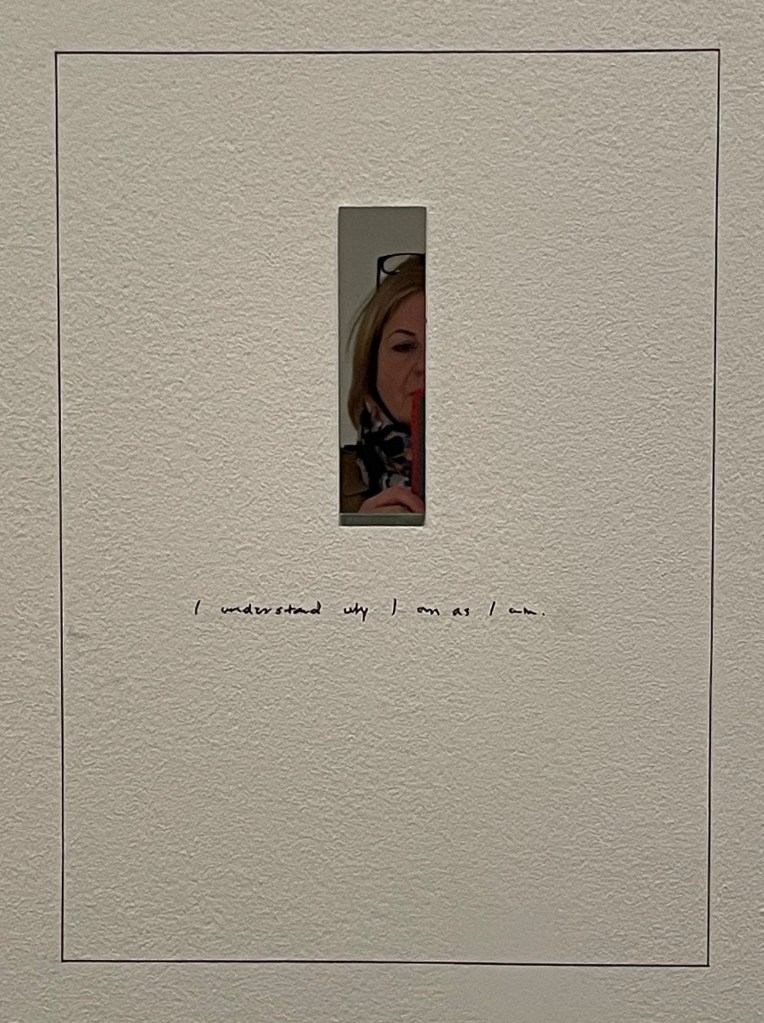

I was particularly drawn to ‘Conviction’, a series of mirrors on paper, as it directly relates to what I’m planning to explore.

’On The Shelf’ comprises 15 milk bottles positioned at a precarious angle on a shelf, but the varying levels of water create a level horizon. The four buckets on the table are actually supporting the table, rather than the other way round. Finally, ‘Box that never closes’ questions what makes a work of art: the box has lost all functionality, and does not even form something that is aesthetically pleasing.

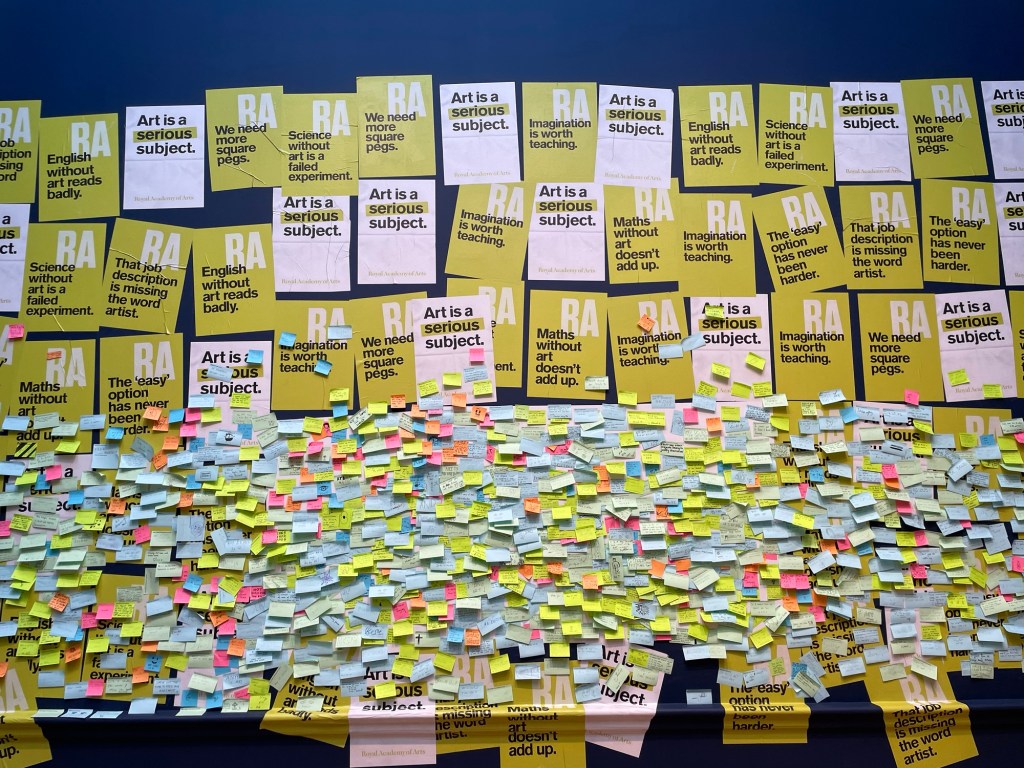

I went into the shop but didn’t buy anything: instead I had a look at the wall which supports teaching art in schools. I put a post-it note up following on from our session a couple of weeks ago: ‘creativity will save the planet’, but I forgot to take a photo.

I was then going to nip into the National Gallery but the queue was half way down the street – probably caused by the extra security and bag searches. So I went round the corner to the National Portrait Gallery which I haven’t been in since its refurb.

I was pleased to see the portrait of zoologist and conservationist, Dame Jane Goodall, by Wendy Barrett, the winner of Sky’s PAOTY 2023. Compared to the photograph taken by Ken Regan, it gives the viewer so much more. I thought it was tremendous, and full of intelligence, sensitivity and humanity.

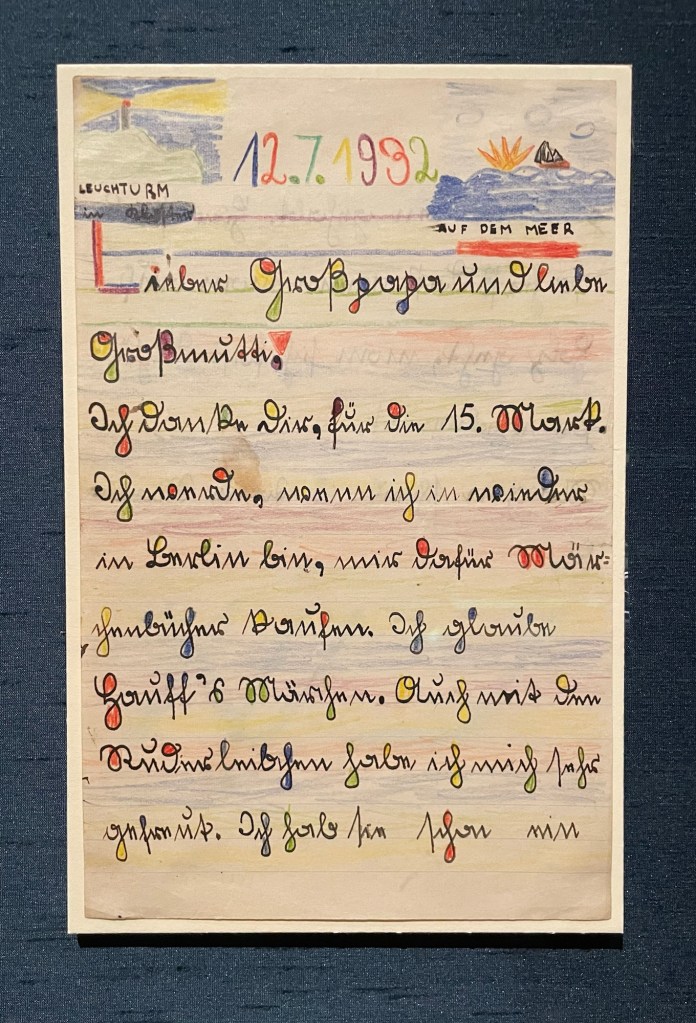

Lucian Freud’s letter to his grandparents, thanking them for the money they gave him, which he was going to use to buy a book of fairytales, reminded me of Miró with its coloured shapes and black lines. It took me back to a hot day in Sóller over the summer when we found relief from the sun in the train station, which happened to be exhibiting various ceramics by Picasso and works by Miró – can’t see that happening at Waterloo Station anytime soon. Freud’s self-portrait is a favourite: the way he applies paint and his minimal brushstrokes are lush.

Bearing in mind my latest experiments using a pen, I was fascinated by the mark-making in Eileen Agar’s drawing of the modernist architect, Ernö Goldfinger. Hockney’s portrait of Sir David Webster with Tulips is stunning: I was a bit perturbed by the size of his head at first, and the fact that the sole of his left shoe seems to be coming away, but I think I’m ok with it now. In any event, it’s all eclipsed by the beautiful rendering of the table and tulips, and the fact that the jacket hanging over the arm of the chair makes him look like he’s levitating.

Colin Davidson’s Silent Testimony was moving: a collection of 18 large scale portraits of individuals who have all experienced loss in the Troubles in Northern Ireland, although it is also more generally about everyone who is left behind after conflict. They are impartial: there is no reference to the sitters’ religion or politics. What is striking is that none of the sitters are looking directly out of the canvas; they look off to the side as though deep in thought, as if they are remembering. There is a real sense of loss and pain, and contemplation – it is etched onto their faces, quite literally in some areas. They are painted in thick paint which seems to be weighing them down. But it’s all about the eyes. They are painted with a much more careful and detailed application of thinner paint. They almost look haunted.

And then I walked back to Waterloo Station, over the bridge, with Ray Davies crooning in my ear, although, let’s face it, his voice isn’t what it is used to be. All in all, apart from my break-up with Michael, a good day.