For the last couple of weeks we’ve been continuing to explore Turner in my painting class. The subject is water and stormy weather. As before, we’ve been applying thin layers of paint and sansador with a rag, and then applying several layers of glazing.

We started with a couple of small studies.

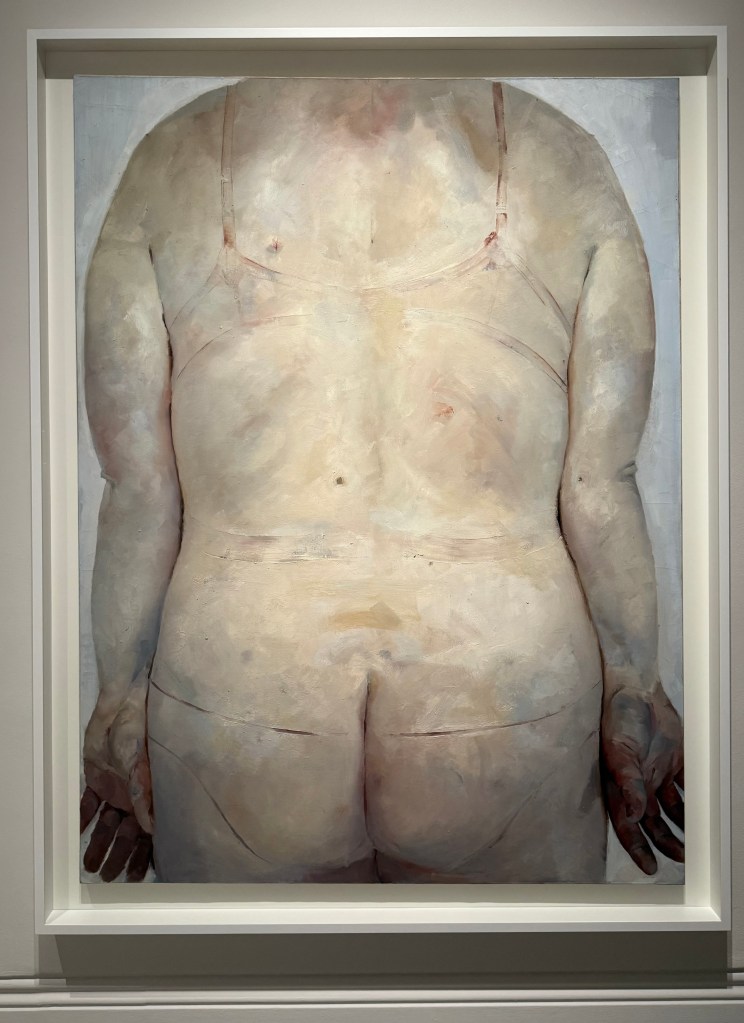

I used a limited palette of mineral colours – ultramarine blue, cadmium yellow light, burnt umber, alizarin crimson and titanium white. I’m not keen on it, it jars with me, in fact, I really don’t like it, but it meets the brief.

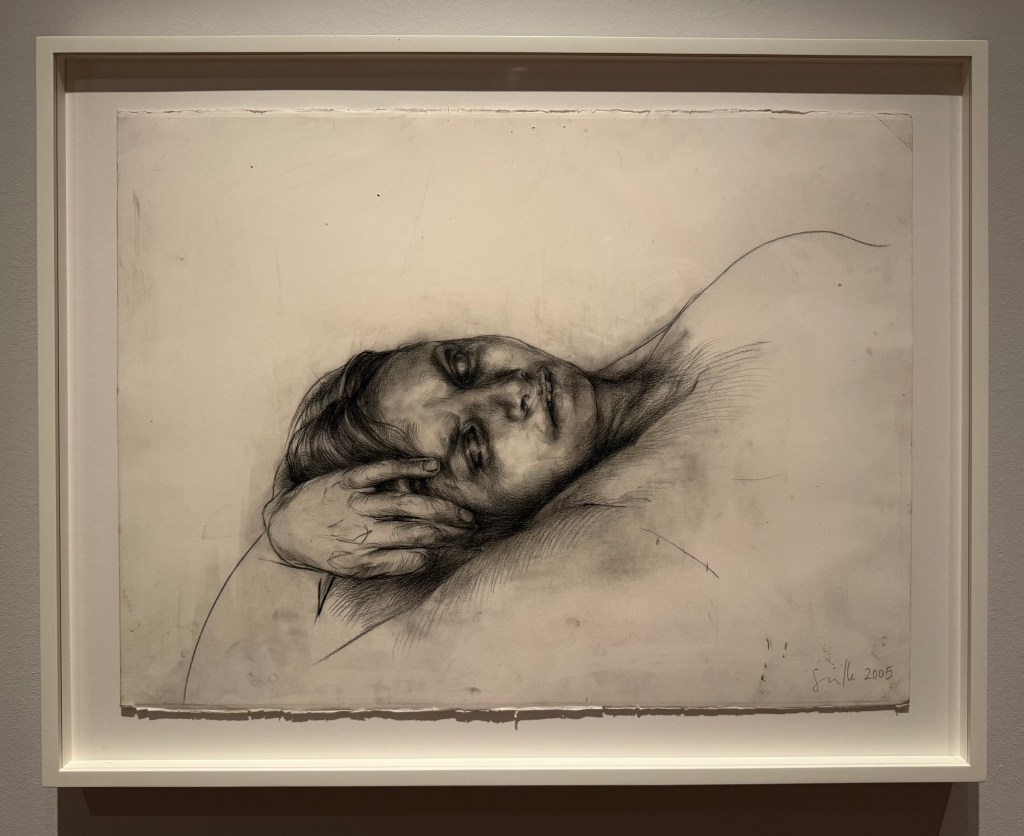

I much prefer this one – to me, it’s less figurative, although as soon as you put in a horizontal it automatically reads as a seascape. A post-Turner palette of cerulean blue, Prussian blue, phthalocyanine turquoise, cadmium free yellow, winsor violet and titanium white.

Then starting with an acrylic ground of a yellow grey, applied thickly and roughly so that definite brushstrokes are visible, I used the same limited palette of mineral pigments as in the first study.

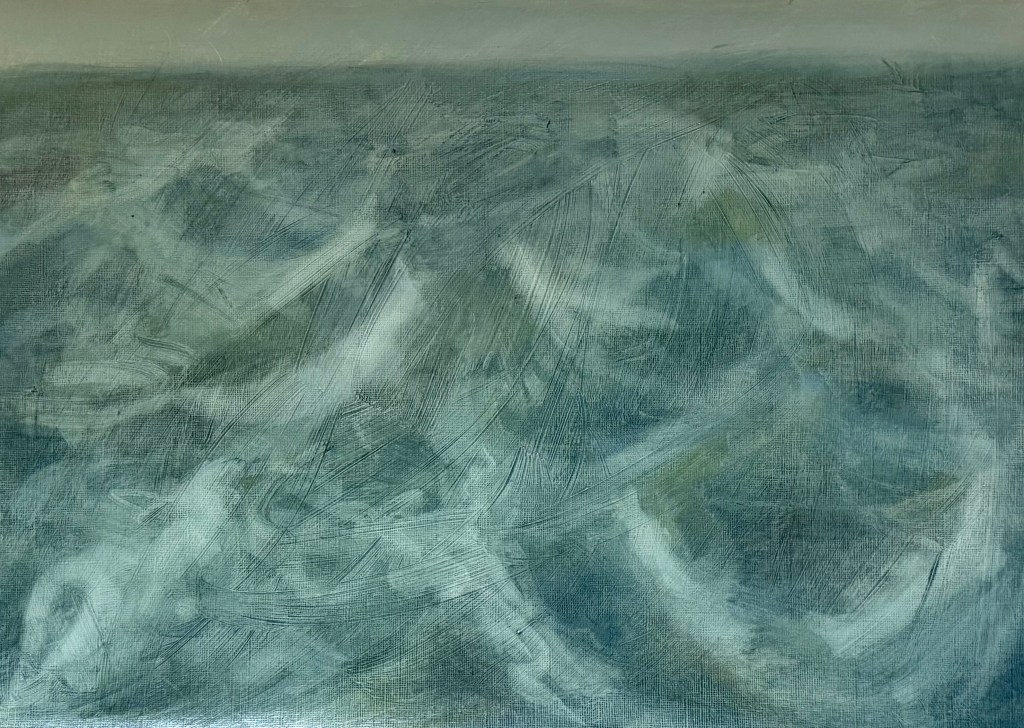

It all started to become a bit twee, for want of a better word, so I blurred the horizon, and tried to break it all up, knocked it back and accentuated the sweeping brushstrokes in the ground using an ultramarine glaze. I feel better about it, but in retrospect maybe I should have done away with the horizon completely, as Turner tended to do, or maybe the horizon allows it some space? I think I need to put it away and reflect on it at a later date.

I’m conflicted; over the last year, I have found that I have been moving away from figurative work, particularly in terms of art that I like to look at, perhaps in an attempt to free myself. I’ve always taken the view that I attend these weekly classes because I like to explore different directions, and that there is no point just turning up and making what I want to make each week regardless. I try my best to complete the task, but I’m finding it increasingly difficult. Maybe this is a lesson for the future – of not always being able to make the work which I want to make.