On the act of creating:

Gompertz reflects on the ability of creatives to think about both the big picture, and the fine detail.

”It requires your mind to constantly go back and forth, one moment concerned with the minutiae, the next stepping away and seeing the broader context… One tiny dab of colour can radically change the appearance of the largest of paintings. Each stroke of the brush is a note struck in a visual concerto; any mistake is as obvious to the viewer as hearing an orchestra member hit a wrong note.”

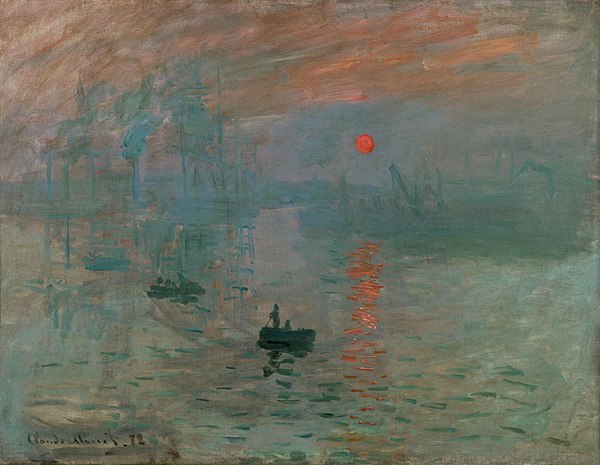

It’s true that the tiniest detail can make a painting: the small detail of the red sun makes this work by Monet.

Sunrise, 1872, Monet (Wikipedia 7 Jan 2025)

Gompertz describes a visit he made to the studio of Belgian artist, Luc Tuymans.

He is intrigued by Tuymans’ work and its ability to make him want to look closer. Tuymans explains that every painting has a point of entry: a small detail that catches your eye and draws you in. He is influenced by other artists who use this trick: Hopper, Van Eyck and Vermeer. In the case of the latter, Gompertz explains that the point of entry for ‘Girl with a Pearl Earring’ might be assumed to be the highlight on the earring but, in fact, conservators uncovered an alternative point of entry: a small dot of pale pink paint in the corner of her mouth, which serves to change the overall reading of the painting.

Detail ‘Girl With a Pearl Earring, 1665, Vermeer

As an aside, to my mind, the point of entry in Monet’s ‘Sunrise’ above is the red sun, going down through the buildings on the right, the reflection on the water, back up to the boat in the foreground, to the boats behind, up to the buildings in the distance, into the sky and following the directional brushstrokes up to the top righthand corner.

Tuymans completes his paintings within the course of a day; he uses the edge of the canvas as his palette which allows him to work quickly, as does his preconceived detailed plan, which can sometimes have begun many months, if not years, before. In fact, Tuymans goes so far as to plan an entire exhibition upfront before he has even started work, from the relationship between each painting, its size, location, the colour of the wall on which it will hang, and so on. His rationale for treating his work as a unit in this way is that to make sense of it, all of the paintings will need to be seen together, and so he increases the chances of there being a major retrospective of his work once he is dead. Now, that’s seeing the bigger picture!

I’m not really sure what I think about this. Planning work in such an extensive and detailed way seems very restrictive to me. Having said that, I would assume that his planning process includes a prolonged period of experimentation before committing to the final piece, which is why he can complete it in a day. He also uses existing images as a basis for his work, which is likely to reduce the number of questions he has to ask himself.

As for the focus on his legacy, I really can’t make up my mind. I suppose it depends on why artists, and in particular, Tuymans, make art. Is it to make the world a better place? Is it to fulfil the need to express themselves? Is it to leave a lasting mark on the world? Is it to make money? Is it because they simply have to? It’s probably a combination of all of these things, with some being of greater significance than others. I just get the feeling in Tuymans’ case that it’s rather contrived, and predominantly about his legacy. I actually wish that I hadn’t read this about him: for me it is a distraction from his work, which is primarily concerned with people, and their relationships with the past.

John Playfair, 2014, Luc Tuymans & John Playfair, 1824, Henry Raeburn (momus.ca 7/1/25)

I’m reminded of Sean Scully. My mother couldn’t stand Sean Scully. In fact, she didn’t rate Picasso either. I remember a conversation I had with her when she phoned me up one morning: she hadn’t been able to get to sleep the night before, so she had got up, made herself a cup of tea and put the TV on. She ended up watching a documentary on Sean Scully. She hadn’t been able to get to sleep after it either, as she had been so incensed by it. Did I know that his paintings, basically just coloured stripes, sold for millions of pounds? I suspect the problem had arisen because the programme makers had juxtaposed some footage of Scully applying some paint to a canvas in a rather sloppy slapdash fashion with footage of one of his paintings being sold at auction. I think it was one of those ‘I could have done that’ moments, but I resisted the urge to give the obvious answer ‘But you haven’t, have you?’, and instead commented that it’s because he is actually a very astute businessman. From what I understand, Scully controls the supply of his art into the art market, retaining a significant number of works himself, thus reducing supply, increasing demand and driving up prices, whilst at the same time ensuring that there is plenty of his work readily available for retrospectives. Basic economics, really.

Song (1985), Sean Scully approx value 2022 £1.6M (sothebys.com 7/1/25)

It all comes down to the uncomfortable relationship between the creation of art and profit, which Gompertz deals with early on in his book, and which I wasn’t planning on covering, but as I seem to have found myself here anyway…

On money:

At it’s very simplest, if you are a professional artist then you need to earn an income from your work to survive. But the relationship between art and money raises so many questions. Is the problem the amount you earn and what you do with it? Which is more worthwhile – the work of a penniless artist slaving away in a garret, or an artist who plays the game and exploits the brand conscious wealthy consumers? Does the need to earn an income compromise or limit an artist’s ability to express themselves authentically? Sophie, in her post reflecting on the first term, refers to the new sense of creative freedom she has experienced, away from the conveyor belt of producing work which would appeal to past and future buyers of her paintings. It is a subject we’ve touched on briefly in our weekly sessions, and it seems a very delicate balance to get right. I think Gompertz probably sums it up best:

“The intellectual and emotional motivation isn’t profit, but it is an essential component. Profit buys freedom. Freedom provides time. And time, for an artist, is the most valuable of commodities.”

In his book, Gompertz explores the issue of artistic entrepreneurism by starting with the artist who didn’t shy away from the subject of money and materialism by making his art all about them: Andy Warhol.

“Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.” Andy Warhol

He then covers the likes of Reubens, an expert salesman, who went off ringing the doorbells of the aristocracy and royalty of Europe whilst his minions worked endlessly in his workshops; Van Gogh and his money man, Theo; and American artist, Theaster Gates, who uses the proceeds of his art to buy and refurbish buildings for use by the community in the South Side of Chicago, where he grew up, thereby regenerating the area and effecting positive social change.

‘Chorus’, 2016, Theaster Gates

I had hoped to have covered much more of the book in this post – it may end up having as many parts as The Godfather! The fact that I have had so much to take note of and comment on, is proof that I am finding it incredibly insightful. I am aware that, at the moment, I’m using this blog for note-making. I have to, otherwise I’ll forget it all. I have lost count of the number of times I’ve read a fact and thought, oh that’s interesting, I must remember that, only for it to disappear again. It infuriates me that I can’t recall facts and statistics at the drop of a hat when having a discussion about something, whilst the other person seems to be able to pluck them out of thin air in support of what they are saying. Or maybe that’s exactly what they are doing – they do say that if you say something with enough confidence people will believe you…