… and Lead a More Creative, Productive Life by Will Gompertz isn’t taking me long to read at all. Gompertz, artistic director at the Barbican, makes some very interesting and thought-provoking observations on what it is to be creative. As I’m galloping through it at such a speed, I thought it best to highlight some parts, as I go along, which I think will either help me in finding my artistic voice, or which reinforce ideas and concepts which we have touched on in the course so far.

On failure:

”When it comes to creativity, failure is as inevitable as it is unavoidable. It is part of the very fabric of making. All artists, regardless of their discipline, aim for perfection…But they know perfection is unobtainable. And therefore they have to accept that everything they produce is doomed to be a failure to some extent…Thomas Edison knew all about the notion of sticking at it…But at no point did he countenance failure: ‘I have not failed 10,000 times,’ he said. ‘I have not failed once. I have succeeded in proving that those 10,000 ways will not work. When I have eliminated the ways that will not work, I will find a way that will work‘…There is plenty of time for wrong turns, for getting lost; for feeling generally hopeless. The crucial thing is to keep going. Artists appear glamorous and blessedly detached, but in reality they are tenacious grafters: they are the proverbial dogs with bones… And while they are out there, worrying away, they often discover a hidden truth about the creative process… Their success is very often down to a Plan B. That is, the thing they originally set out to do has morphed along the way into something different.”

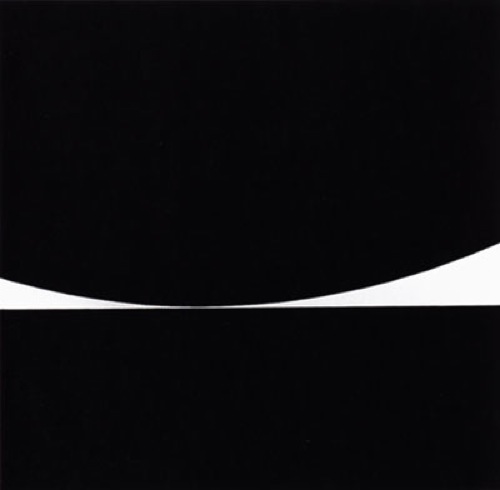

He references several artists who started out in one direction only to find their success through a Plan B, such as Mondrian, Lictenstein and Bridget Riley. In the case of the latter, in the early part of her career Riley was interested in colour theory and the work of the Impressionists, the Pointillism of Seurat, and the composition of Cézanne. It wasn’t working for her; she was directionless and lacked originality, and she was getting older. The ending of a relationship caused her to paint a canvas black, and she took all that she had learnt from her studies of Seurat et al and applied her knowledge in abstract terms. She painted a white horizontal line the lower edge straight, the upper edge forming a curve – it became a painting expressing the dynamism and inequality of relationships, human and spatial.

’Kiss’, 1961, Bridget Riley (Wikiart 4 Jan 2025)

”Bridget Riley had to abandon the one thing she thought most important and appealing about painting – colour – in order to make any real progress. It didn’t mean colour could never feature in her work again, only that at that precise moment in time it was the roadblock… Only when [she] went back to the most basic of basics – a canvas covered in black paint – did she find the necessary clarity to progress. Only then did she discover the most precious and liberating of things: her artistic voice… As long as you stick at what you are doing, constantly going through the cycle of experimentation, assessment and correction, the chances are you will reach the moment when everything falls into place.”

The cycle of experimentation, assessment and correction is at the very essence of this course: Practice-based research.

Gompertz also states that if you call yourself an artist and make art, then you are an artist regardless of where you are in the process, or what skills you still need to learn and develop. I think I find this the hardest to embrace – I still can’t quite think of myself that way. I’ve only just got my head around being a student – in retrospect, it probably wasn’t the best idea to try it out first on the border official at Marrakech airport who looked at me with incredulity and repeated “Student?”. Admittedly, it’s been a lot easier since I discovered all the discounts available!

On ideas:

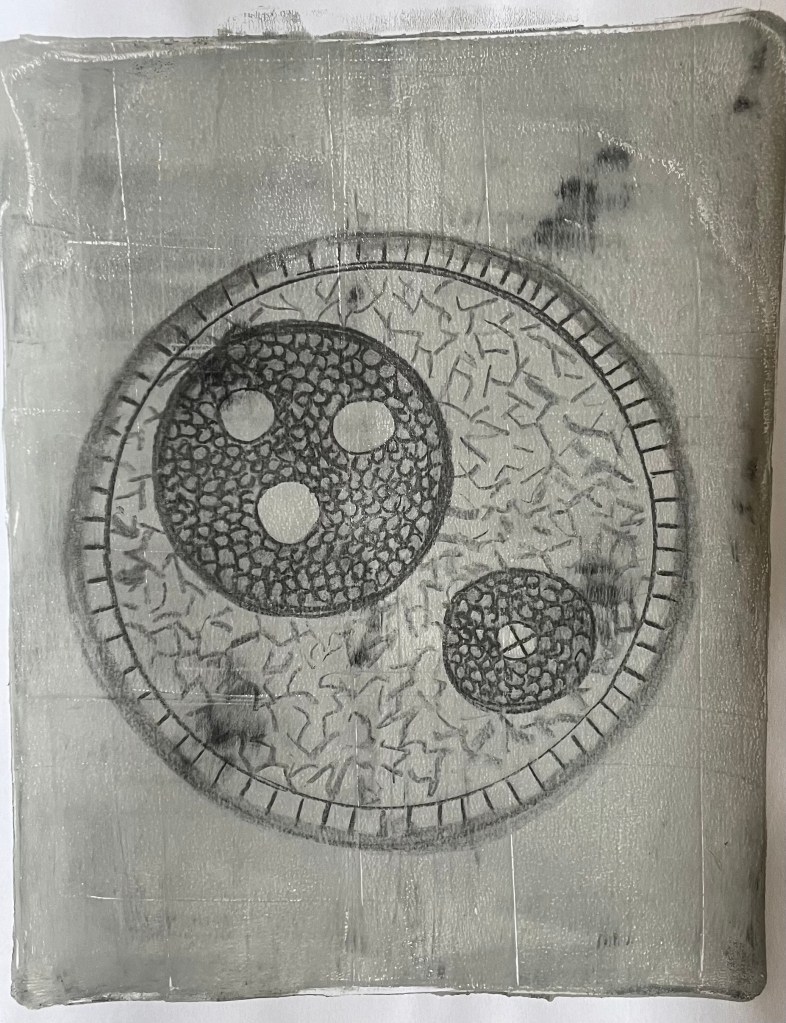

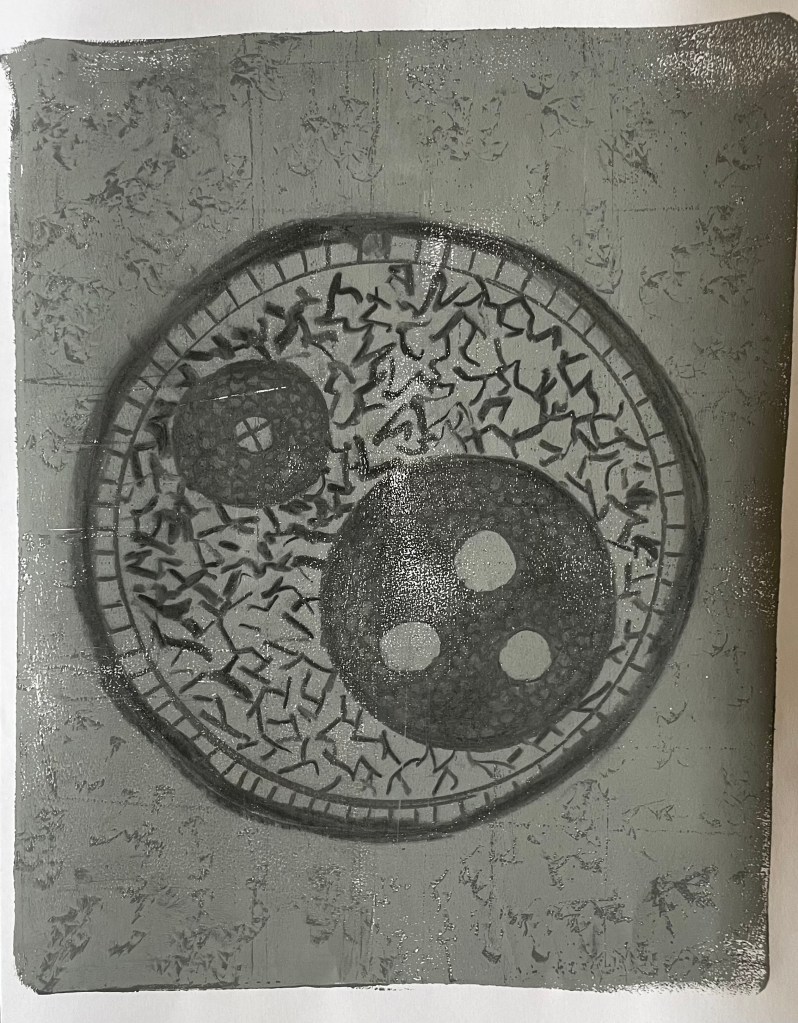

Gompertz asserts that originality in a completely pure form does not exist; that all ideas are additional links in an existing chain, each link adding to the one before. It is a form of disruption: something to react against and respond to, to build upon. He suggests that Picasso, in the quote attributed to him – good artists copy, great artists steal – is actually describing a process that an artist needs to go through: we learn through copying and imitating, and it is only once we have done this and developed the basic techniques that we can identify opportunities to add our own link to the chain, and to find our own artistic voice. This reminds me of my discussion with Jonathan about Frida Kahlo’s ‘The Two Fridas’, when I questioned whether any work I make which is inspired by it will be original enough: he advised me that Kahlo painted it in the late 1930s and I would be doing my version almost 90 years later expressing my own feelings – following Gompertz’s reasoning, I would, in effect, be adding my own link to her existing link in the chain.

In fact there are numerous creatives who have been quoted as admitting to building on the ideas of others.

” If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” Isaac Newton

“ Creativity is knowing how to hide your sources” Einstein

”We have always been shameless about stealing great ideas”. Steve Jobs

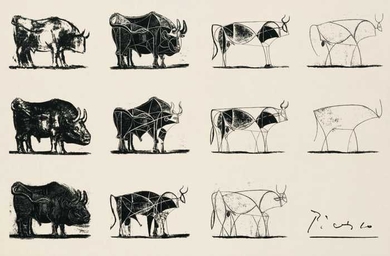

The young Picasso produced work which imitated the likes of Goya, Velázquez and El Greco, and later the Impressionists and Post Impressionists. It was only when his friend, Casagemas, died that he found his own artistic voice in his Blue Period; the blocks of colour, bold lines and expressive manner, which he had learnt from all those artists he had imitated, still influenced him, he just put his own twist on it. He took their ideas and filtered them through his own personality and experience, and used his instincts to simplify and reduce them into his original thought, into new and unique connections. Being creative isn’t always about adding to something; it can be at its most original when taking something away. This is demonstrated perfectly by Picasso’s bull lithographs, which took him a month to complete.

‘Le Taureau‘, 1945/46 (Wikipedia, 5 January 2025)

”There is no such thing as a wholly original idea. But there is such a thing as unique combinations.” Gompertz