I have just returned from an amazing 4 nights in magically festive Vienna, having had my fill of glühwein, Sachertorte and boiled beef broth (it loses something in translation!).

I’ve never been before, but will definitely be going back. Beautiful architecture, and so much to do, not least the seemingly endless supply of museums and galleries.

The Leopold and Belvedere were on my hit list as housing the greatest number of works by Klimt and Schiele. I had a nagging fear that the episode might end the same way as Michael Craig-Martin but, instead, I came away with a greater appreciation of all the details that can’t be gleaned from a photograph: the brushstrokes, the surprising thickness and coverage of the paint, sometimes leaving areas of the canvas exposed and the purity of colour. It was a revelation to get up really close and just look.

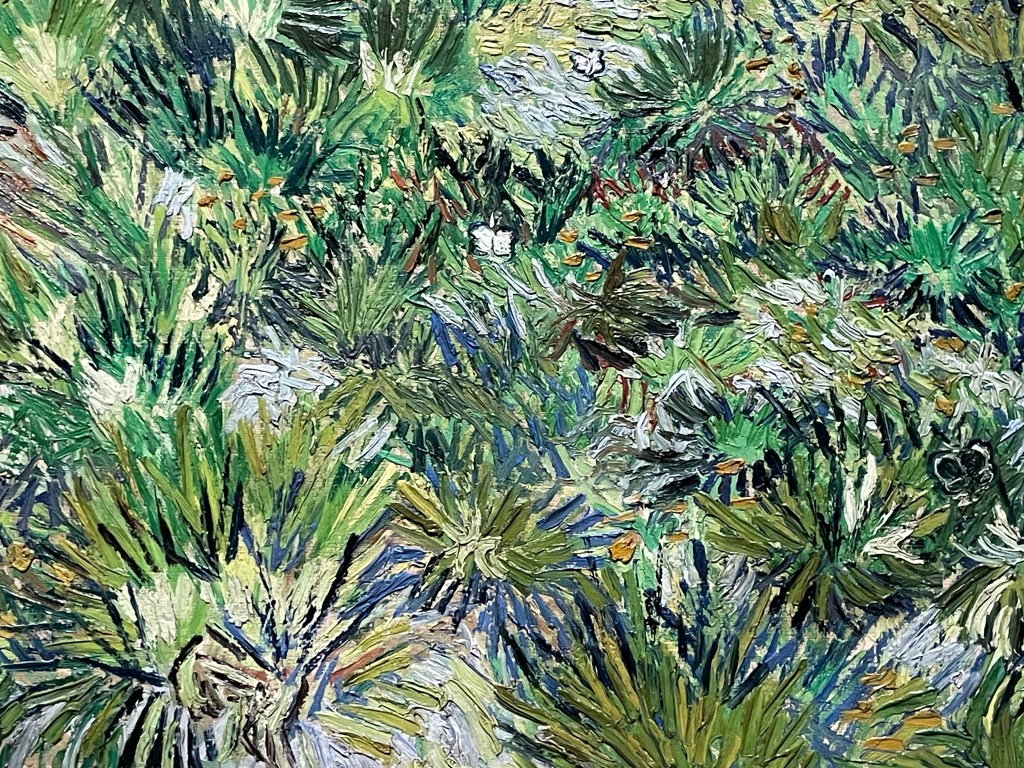

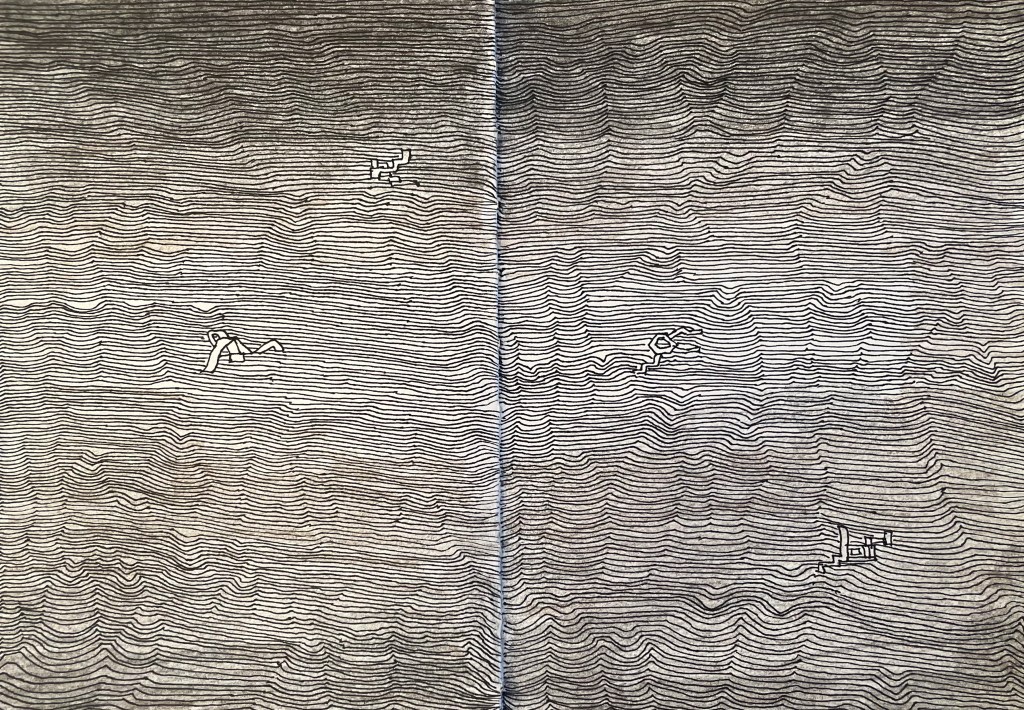

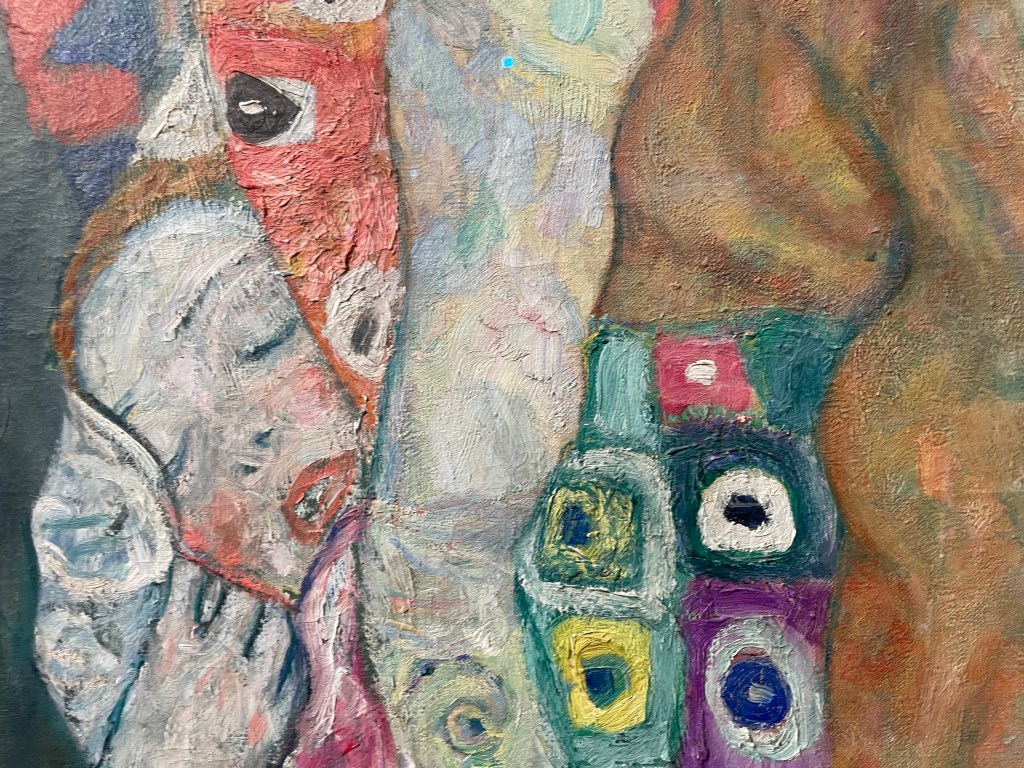

Death and Life 1910/15 , Klimt

Detail

I had always thought that Klimt applied paint quite uniformly and flat, so I was surprised to see the thickness of the paint and multi-directional brushstrokes. I like the way Klimt paints skin in all its imperfections and blotchiness, ranging from the pale and cold whiteness to the warmer, darker tones of the male figure.

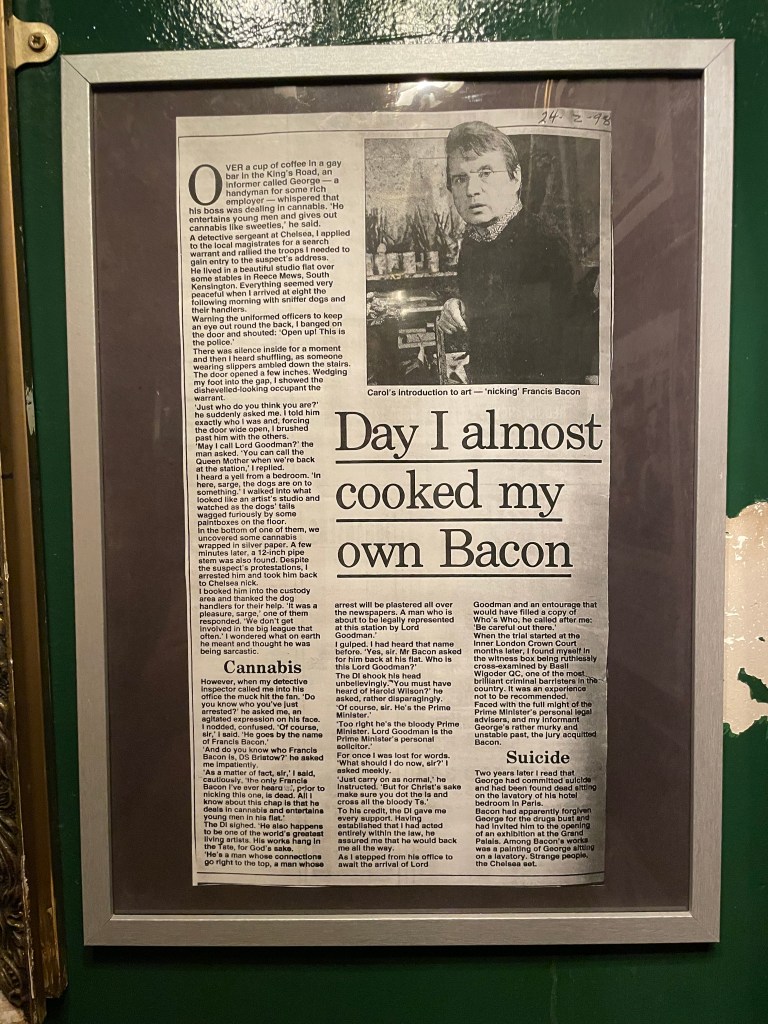

Seeing ‘The Kiss’ was an interesting experience; it reminded me of when I saw the ‘Mona Lisa’ in the Louvre. Being one of Klimt’s most famous works, along with the ‘Mona Lisa’ and Van Gogh’s ‘Starry, Starry Night’, it is one of the most mass reproduced images of all time. I was underwhelmed, and I found it quite sad, as I was expecting to be bowled over by it. It was the most crowded room at the Belvedere, but what I found particularly interesting was that the crowd of people in front of it, holding up their phones and cameras, seemed totally uninterested in looking at it in any great detail – in fact they had left a sizeable gap in front of it so that they could get it in shot. This was handy as it allowed me to perform a flanking manoeuvre to get in front of it, to try and appreciate it as a work of art, as opposed to just a selfie opportunity with a celebrity. There was no point taking a photo – it was so strongly lit, and the lights reflected in the glass covering it. I grappled with my feeling of ‘numbness’ for the rest of the day, and as I was mulling it over in my mind, holding yet another mug of mulled wine in my hand, the answer came to me when I remembered John Berger’s ‘Ways of Seeing’ in which he considers the effect of reproduction:

”When the camera reproduces a painting, it destroys the uniqueness of its image. As a result its meaning changes. Or, more exactly, its meaning multiplies and fragments into many meanings … Alternatively one can forget about the quality of the reproduction and simply be reminded, when one sees the original, that it is a famous painting of which somewhere one has already seen a reproduction. But in either case the uniqueness of the original now lies in it being the original of a reproduction. It is no longer what its image shows that strikes one as unique; its first meaning is no longer to be found in what it says, but in what it is.”

By contrast, in the next room was one of my favourites, ‘Judith and the Head of Holofernes’, a depiction of a strong femme fatale, the polar opposite to ‘The Kiss’.

Judith and the Head of Holofernes, Klimt, 1901

What can I say? I love gold leaf: I’m a magpie. Despite the abundance of gold in the painting, the eye is still drawn to the figure of Judith which is thrown forward by the decorative background. She is holding the head of Holofernes, somewhat gently, which is shown half in and half out of the frame, relegating him to a secondary role in the drama which has unfolded. There are intriguingly two decapitated heads in the painting; the treatment of the choker has effectively severed Judith’s head from her body. It is an image full of female power, sexual and otherwise.

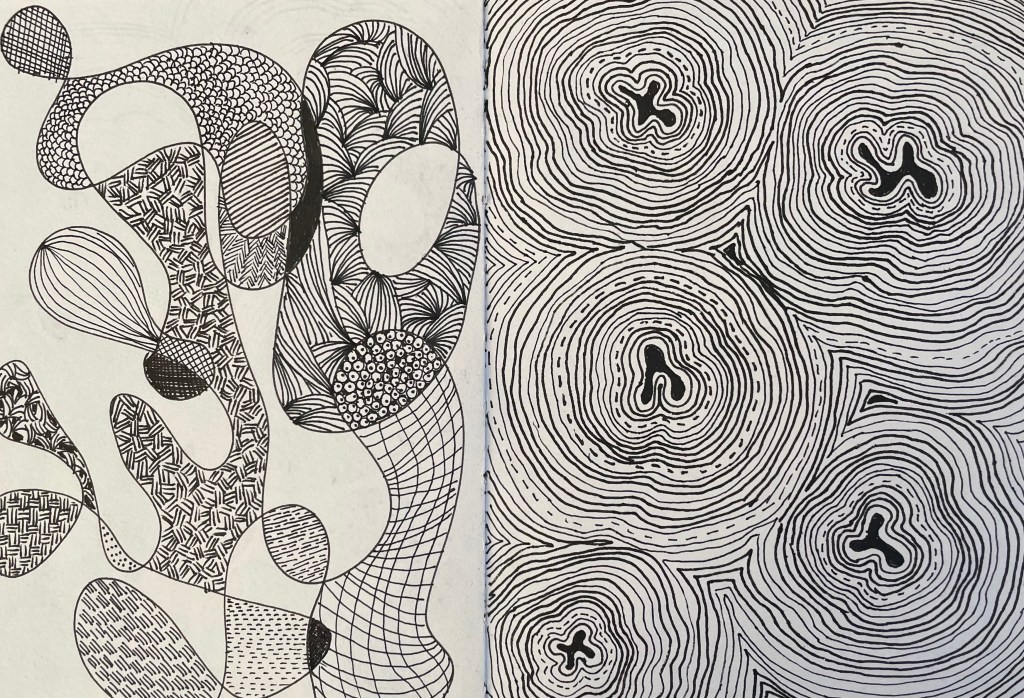

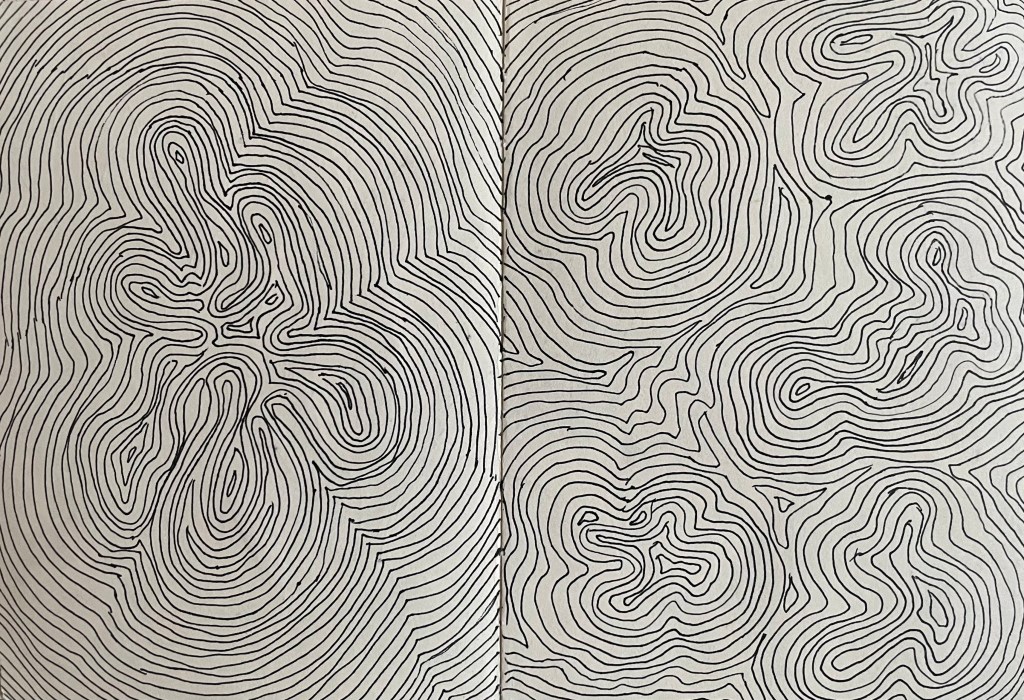

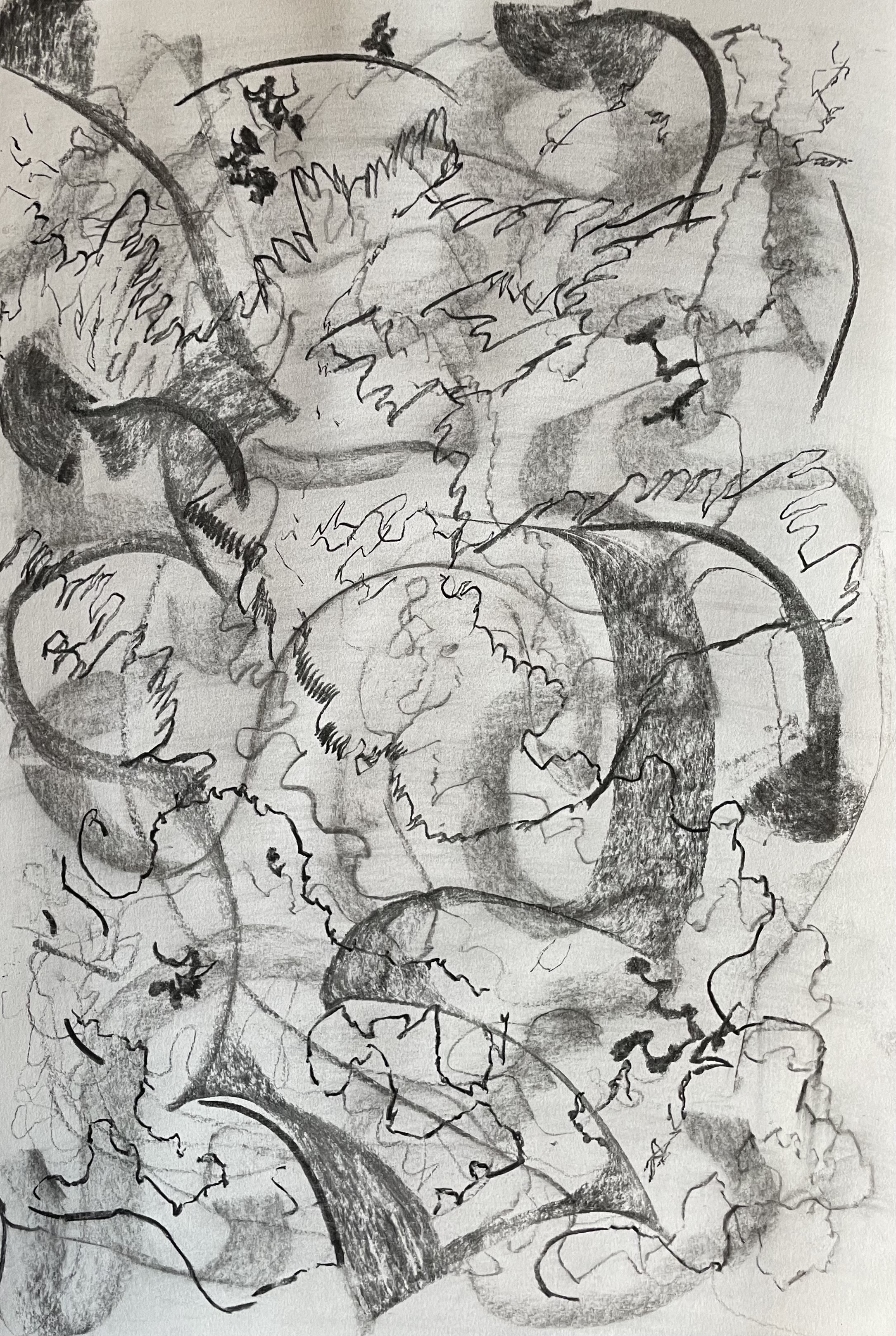

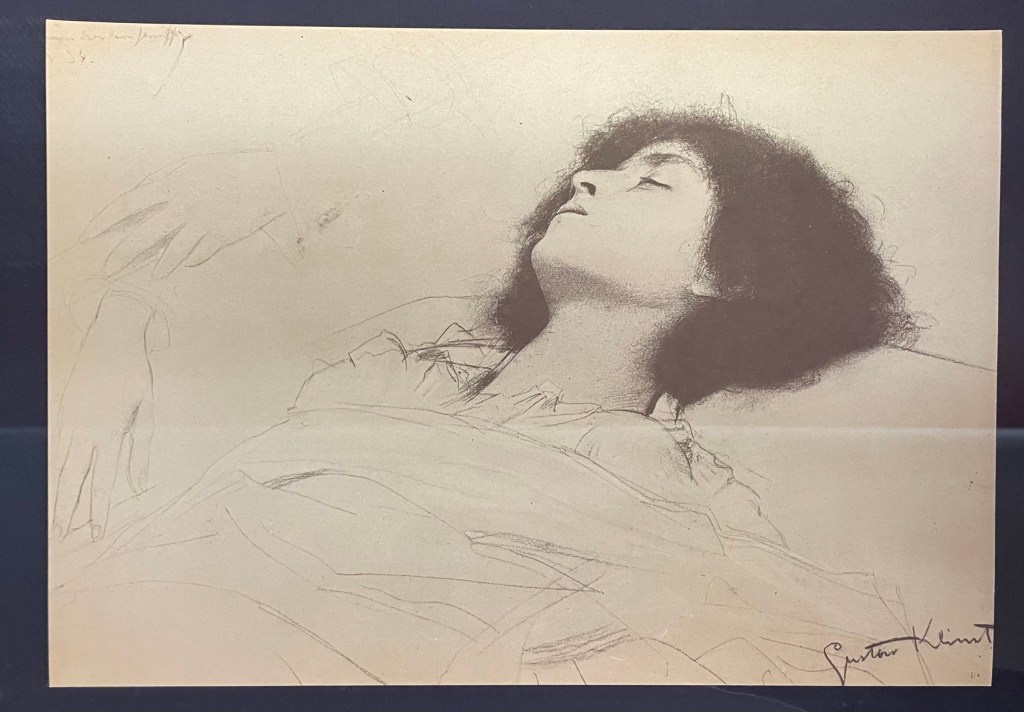

It’s easy to forget that Klimt was a master draughtsman.

His drawings are exquisite. The simple monochrome of pencil or black chalk, a quiet antidote to the noise of gold and vibrant colour.

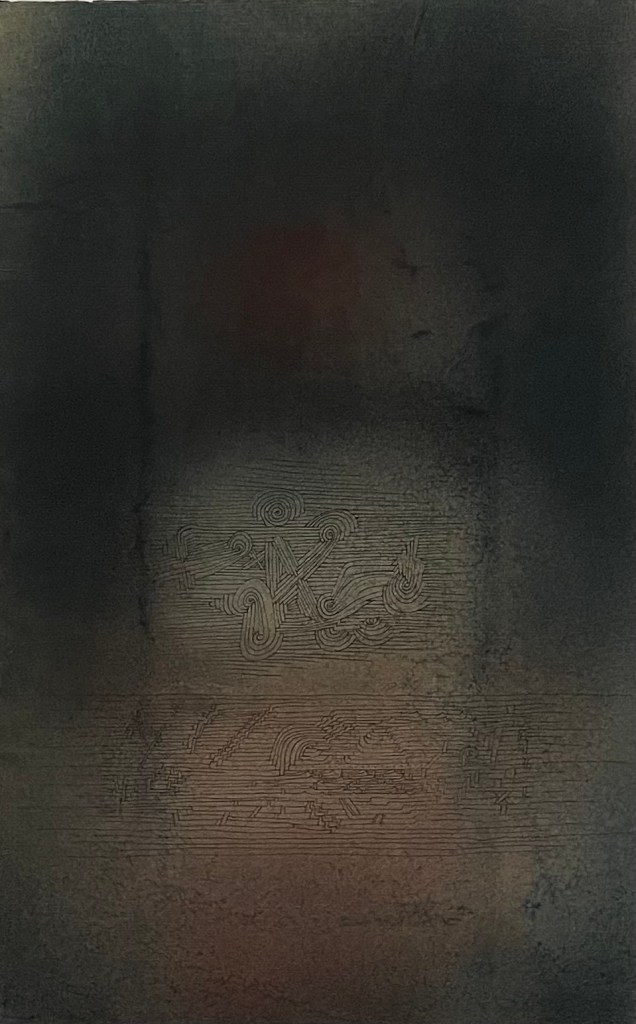

Self-Portrait with Raised bare Shoulder, Egon Schiele, 1912

I love this self-portrait; it is so expressive, and the fluidity of the brushstrokes creates a sense of movement and vitality. It is reminiscent of the Lucian Freud self-portrait in my earlier post, “I’m Sorry, Michael…”. It is quite small but he manages to pack a lot into such a confined space, including his shoulder, which by extension includes his body. The difference in treatment between the figure itself, which is quite thinly painted, and the more heavy impasto in the background is extremely effective. It is painted on wood, which might explain the wonderful textures on the face which would have been caused by the hog bristles in the brushes, although I have read, in a book on artists’ palettes, that Schiele would often use a brush to remove paint from a canvas in order to create texture. I particularly like the simple use of sgrafitto particularly above his left eye, and to delineate the edge of the chin against the neck.

The description next to this piece was interesting in that it described Schiele’s connection with his own body as both a fusion and a dissociation, in the context of the main theme of Viennese Modernism ie the individual becomes a dividual – something that can be divided.

The Embrace, 1917, Egon Schiele

This painting is so impactful. It’s approximately 1.5m by 1m. It shows Schiele with his wife, Edith Harms, in a loving and tender embrace. Unlike a lot of his work, this does not, to me at least, have any sexual or erotic overtones. There is a sense of completeness, in that Schiele depicts himself physically emaciated as he envelops and buries his head in the hair of his wife, almost blending into one, in an act of nourishing love. It’s even more poignant to think that this is one of his last works, as they both died within days of each other a few years later in the flu epidemic of 1918-20. He was only 28.

Both Schiele and Klimt were ahead of their time; they were disruptors. Schiele was akin to Sid Vicious and the punk movement, and Klimt founded the Viennese Secession, breaking away from the constraints of the Künstlerhaus. In today’s art world there is no prescribed way of doing things, no longer any art movements or – isms against which to rebel; artists have never been freer to express themselves in whatever way they wish, so I wonder how it is possible for an artist to stand out; how to make a difference in a world of differences.