I didn’t expect to enjoy the Edward Burra exhibition at Tate Britain. His earlier works of figures in bars and cafés in France and the US were interesting, but I was particularly intrigued by his work during the Spanish Civil War, the Second World War, and his later work. He was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis as a young boy, and during the war his medication was subject to rationing which meant that not only was he isolated from his friends, but he was also in pain for most of the time.

He mostly drew from memory, and used watercolour to build up layers. They were extraordinary. They had the solidity of oil paintings, and yet had a remarkable quality of luminescence about them.

As he got older, and couldn’t travel abroad because of his failing health, he went on road trips with his sister, often accompanied by friends. When they stopped to enjoy the views he would just look, later recreating the scene months later in his work.

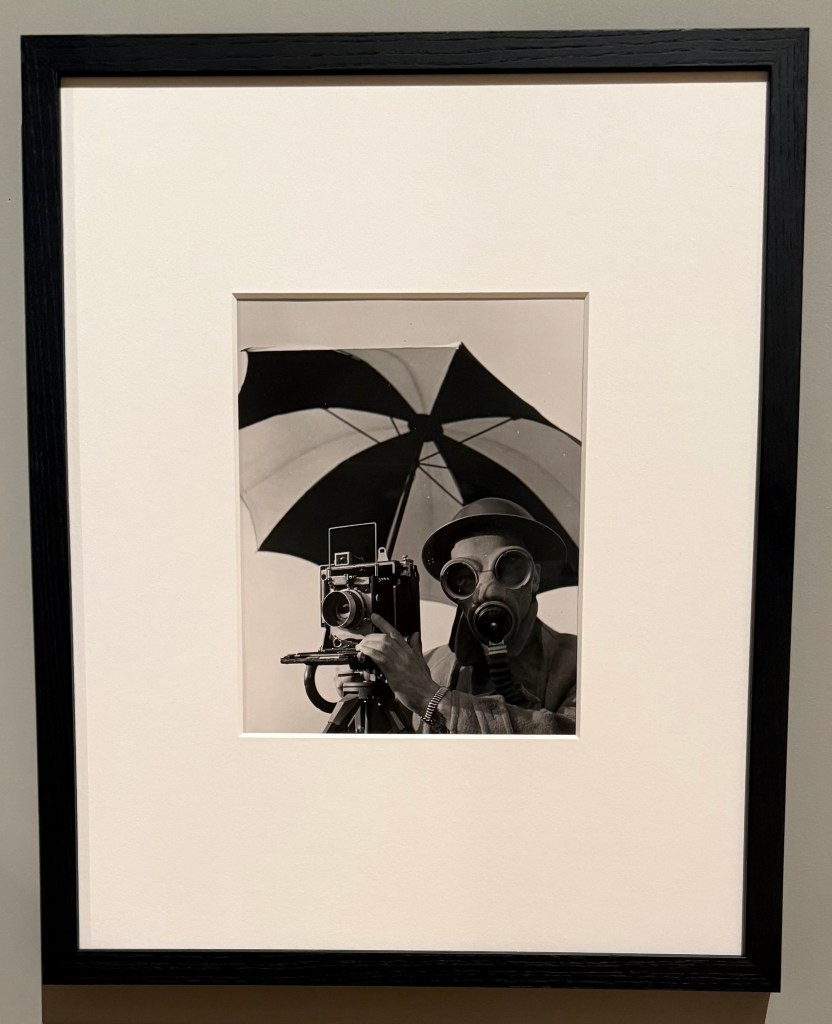

I then went round the Lee Miller retrospective which has around 250 photographic images on display. Originally a Vogue model, she moved from being in front of the camera to being behind it, working closely and experimenting with Man Ray in Paris. During the Second World War she was a war correspondent for British Vogue taking photographs of the Blitz, the liberation of Paris and the concentration camps at Buchenwald and Dachau.

I hadn’t really been aware of Lee Miller before I went to see the film Lee, in which Kate Winslet plays her. At the end of the film, you see a selection of some of her most famous photographs including the one of her bathing in Hitler’s bath taken by her colleague, David E Scherman, as well as the scenes she witnessed at Buchenwald and Dachau, the mud of which is still on her boots which she has purposefully placed in front of the bath. Seeing them in the flesh, in a small side room, was incredibly moving. Not surprisingly, photography was not permitted in this part of the exhibition.

British Vogue was reluctant to publish her photos of the concentration camps, on the basis that people wanted to move on from the war, and whilst they published a few, American Vogue published a comprehensive spread of them in the June 1945 issue, including the most harrowing, under the title ‘Believe It’. Her work, particularly her war photography, was not widely known about until after her death when her son found her collection of photographs. She had given up photography, too traumatised by what she had experienced during the war, and taken up gourmet cooking.

I finished off the day by having a look around the general exhibition and came across the subject of one of my favourite Fake or Fortune episodes (other than Frink’s Warrior found at an Essex car boot sale), Emma Soyer’s Two Children with a Book.