That wasn’t how the last couple of days were supposed to have gone.

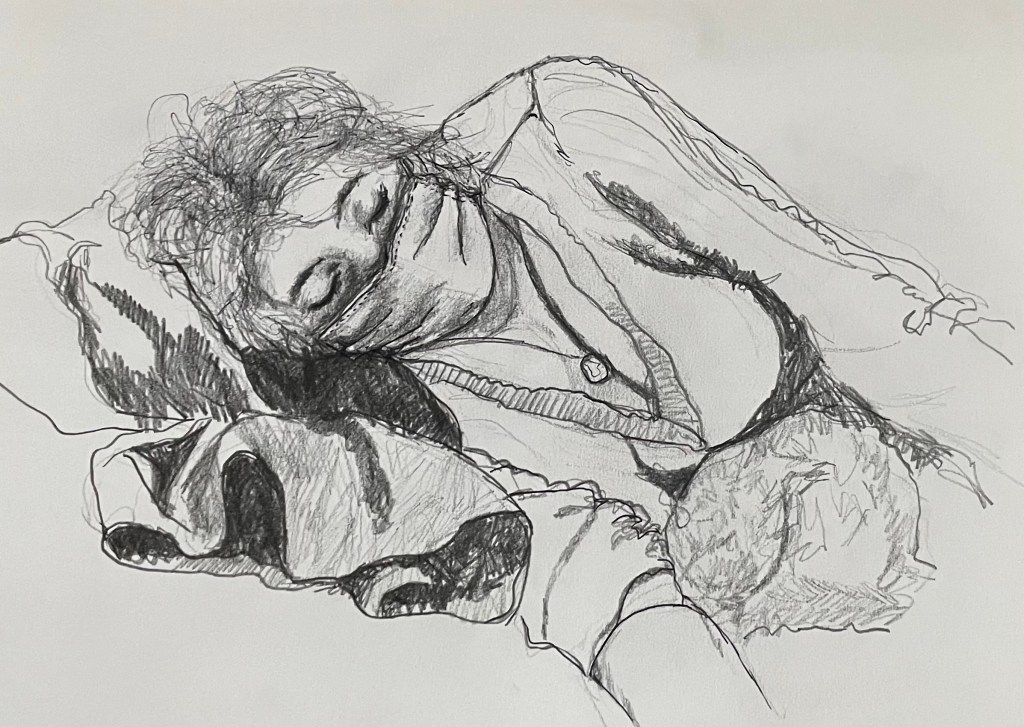

My daughter came home from uni just after our session ended on Tuesday with rapid onset tonsillitis. By Wednesday she was in tears. She is one of the bravest and most stoical people I know, so this unsettled me. It’s heartbreaking watching your child suffer in pain. When I was in pain, my mother used to tell me that, if she could, she would swap places with me. I wish I could say the same, but the truth is my daughter is far better equipped to deal with it than me. When it comes to pain, I don’t mind admitting that I’m a wimp. If there are drugs going that will make me feel better, just pump me full of them – that’s what advances in medical science are for, after all.

I don’t care that I didn’t have a ‘natural’ birth, without pain relief; that she came out of the sunroof. I wasn’t ‘too posh to push’ – she wasn’t going anywhere, and at risk of becoming distressed, and would it have mattered if she hadn’t been, anyway? Is a natural birth somehow superior to one with medical intervention? Why are we told, in that patronising way, that we are not the only woman to have ever given birth? I am the only ‘me’ to have given birth.

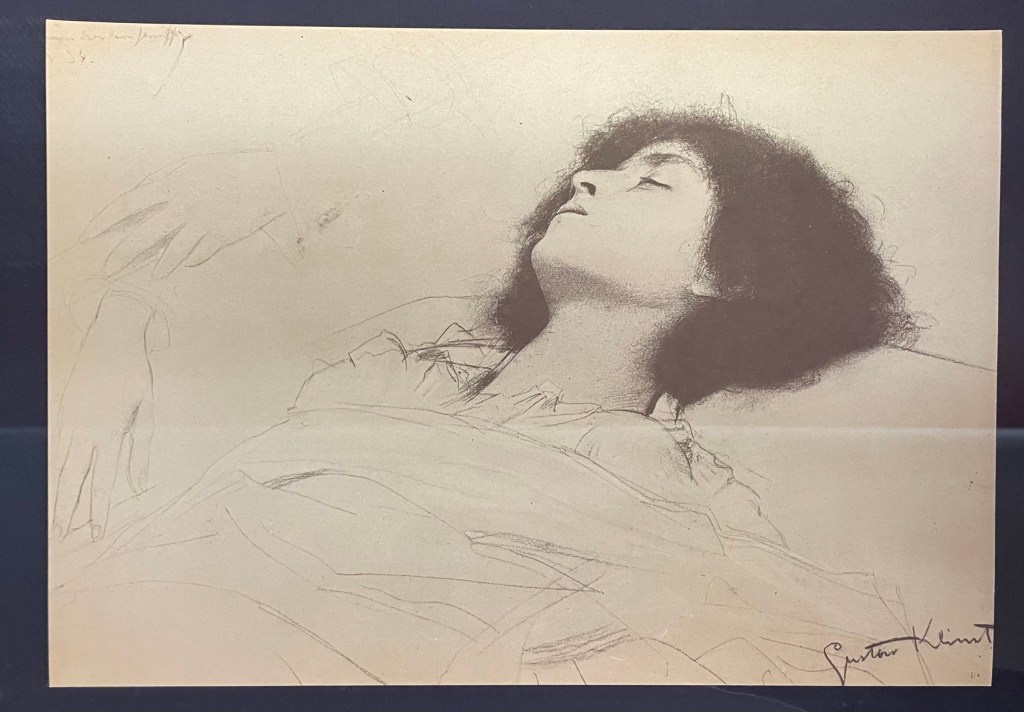

Whilst I’m doing my best to keep negativity out of my life, some things do just make me angry. I think it is now generally accepted that women are expected to put up with an unnecessary level of pain when it comes to matters of their health, just because they are women. Studies have shown that women experience pain more intensely, and for more of the time than men. However, they are less likely to have their pain scores recorded, or to be prescribed pain relief than men. Apparently, this is based on the misguided notion that women are more emotional, which means that they may exaggerate the pain they are feeling – after all, ‘hysteria’ comes from the Greek word hystera, which means uterus. Really? There is now a term for this way of thinking: medical misogyny.

It reminds me of a comment made by a male healthcare professional whilst discussing pain relief during the discharge process after an exploratory procedure, which had been initially attempted without sedation. Some women can ‘tolerate’ the ‘discomfort’. I wasn’t putting up with the intense pain. Did I feel like a failure, that I’d somehow let myself and womanhood down; that I should have been able to ‘tolerate’ the ‘discomfort’ like all those women who had gone before? Initially, yes, and it is very intimidating to be in a situation where you are surrounded by healthcare professionals, both men and women, where you feel that you have lost agency over what is being done to your body. Did I look in their eyes for judgement, particularly in the women’s, whilst I dressed, gathered my things and left? Yes. But the word ‘no’ is empowering, and so it was sedation for me. Anyway, getting back on point, I think I made some quip as to knowing what pain feels like, being a woman. He must have interpreted that comment as alluding to a badge of honour as to the amount of pain women can tolerate, as he replied, something along the lines of: “Women can’t have it both ways”.

Anyway, I’ve managed to make it all about me again; that wasn’t how this post was supposed to have gone. After several trips to, and many hours spent in A&E, pain relief, antibiotics, fluids, steroids, and a bit of an exploration up her nose and down her throat with a camera, she’s thankfully on the mend with plans to whip the little troublemakers out in due course.