I was very lucky to have Cheng and Dalal in my group for this week’s group crit.

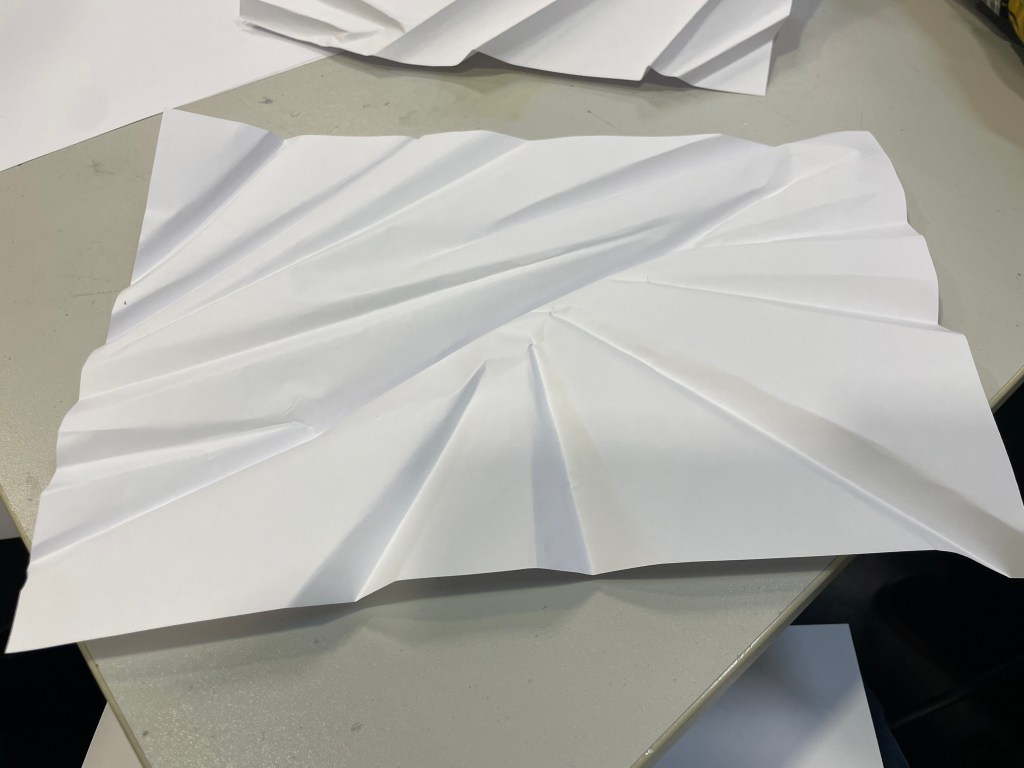

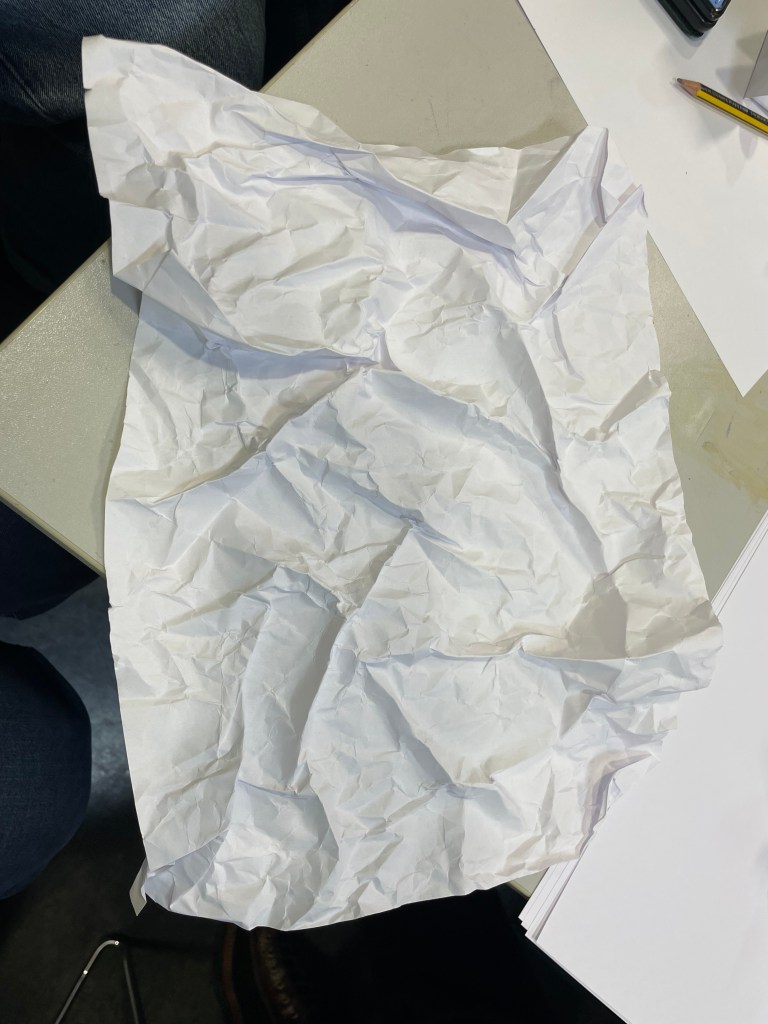

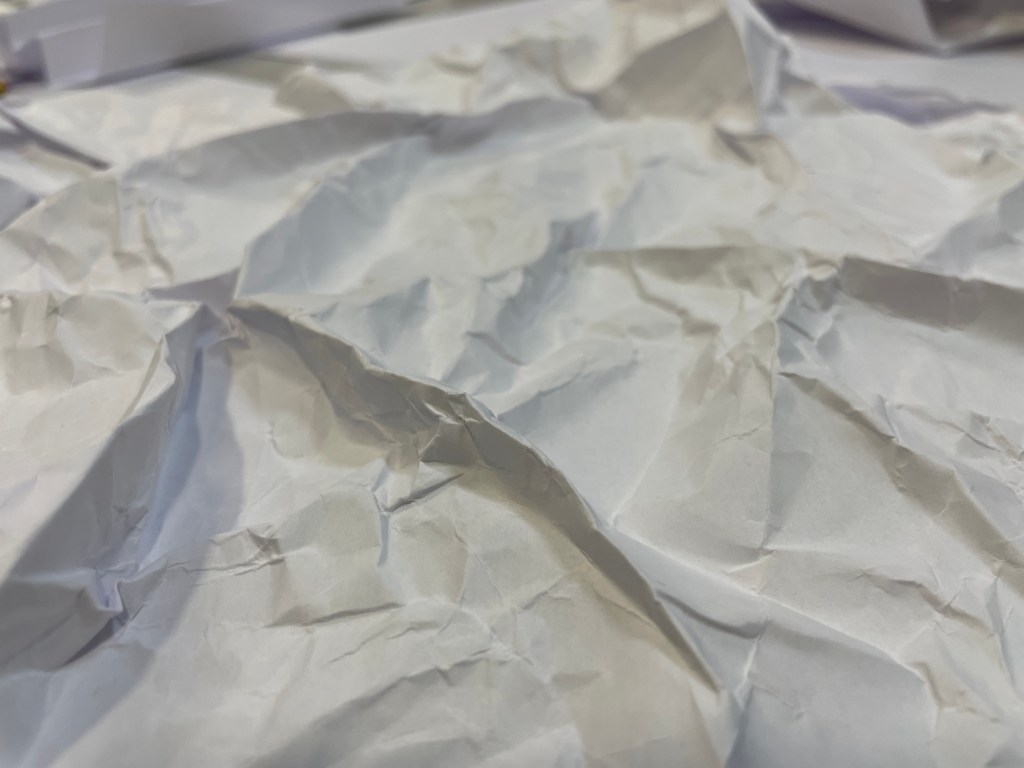

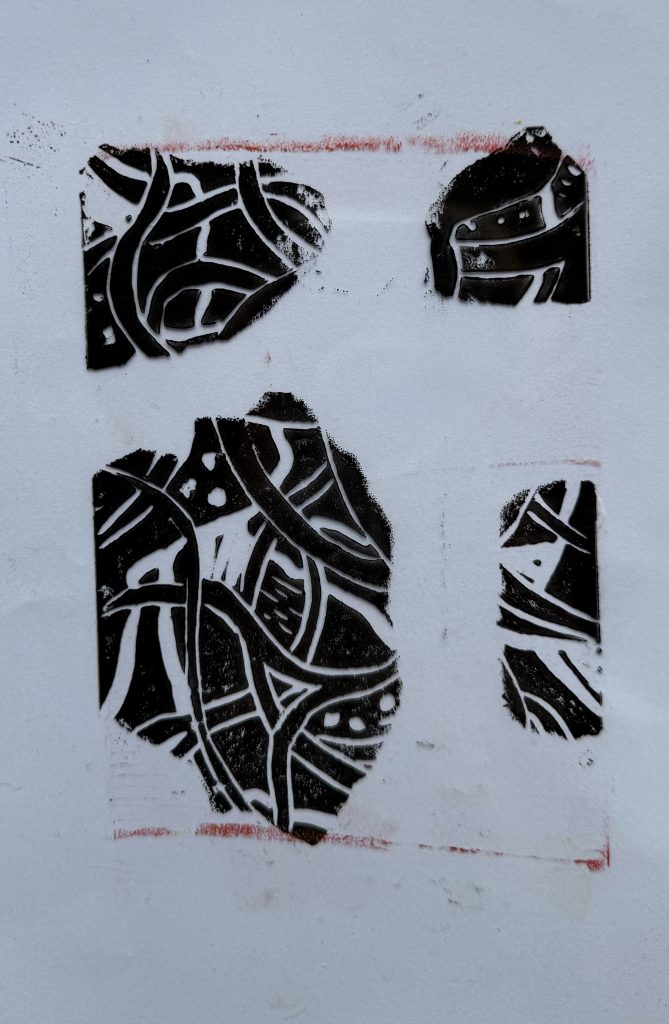

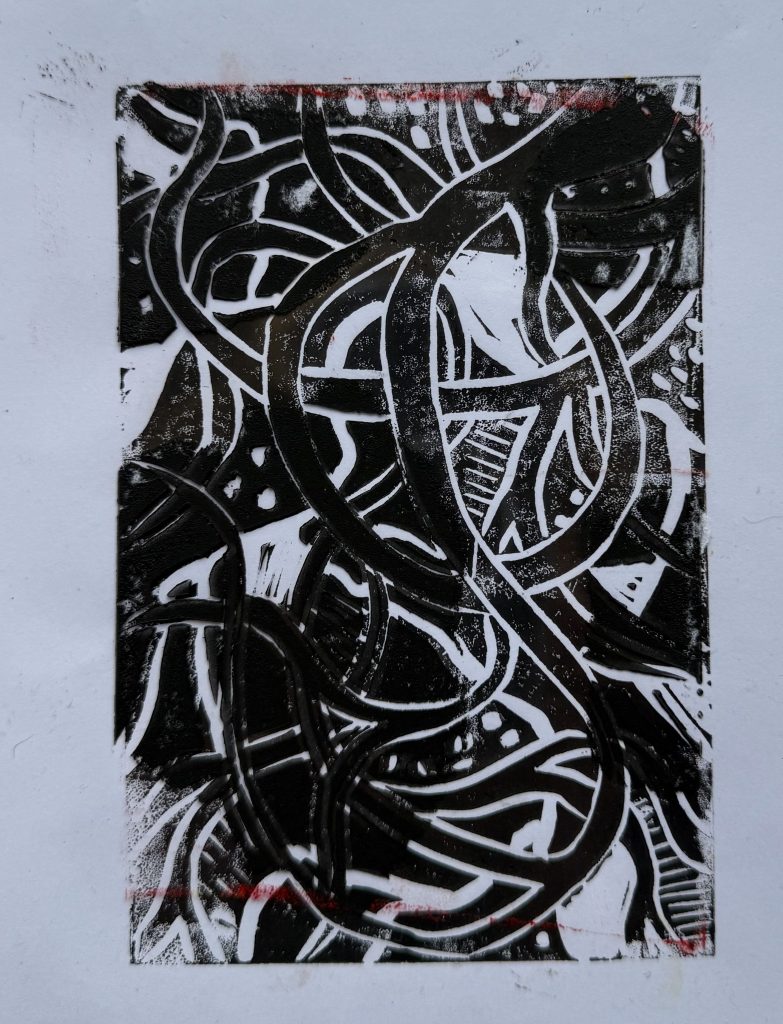

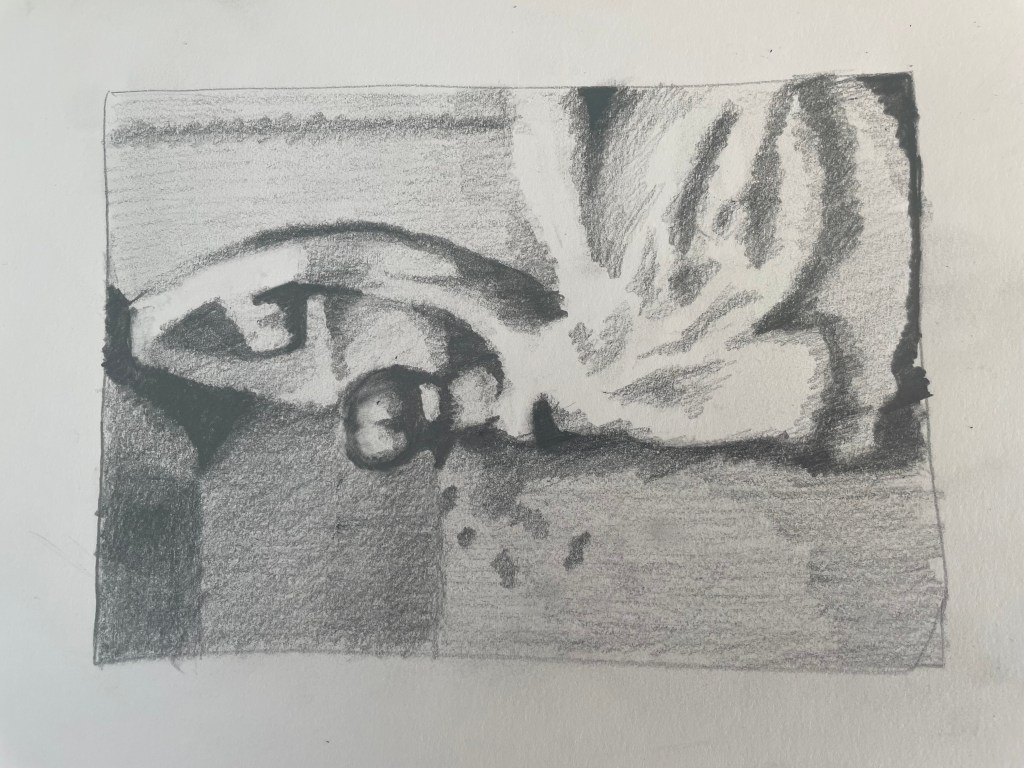

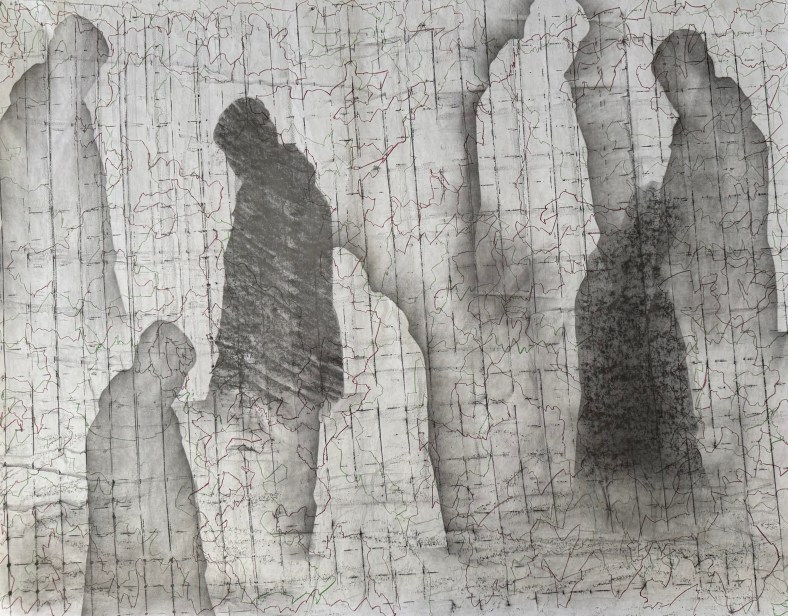

I showed my recent experiments with graphite and pencil.

I explained that I have become interested in the idea of inheritance recently and mentioned Donald Rodney’s work. We had a really interesting discussion about where we come from and our legacy, how it’s sometimes comforting to know that someone else before us was like us which frees us from feelings of fault and guilt, the idea of all that has gone before distilling down into us, much like our family tree before us, ends with us. How what we pass on feels like a responsibility or a burden.

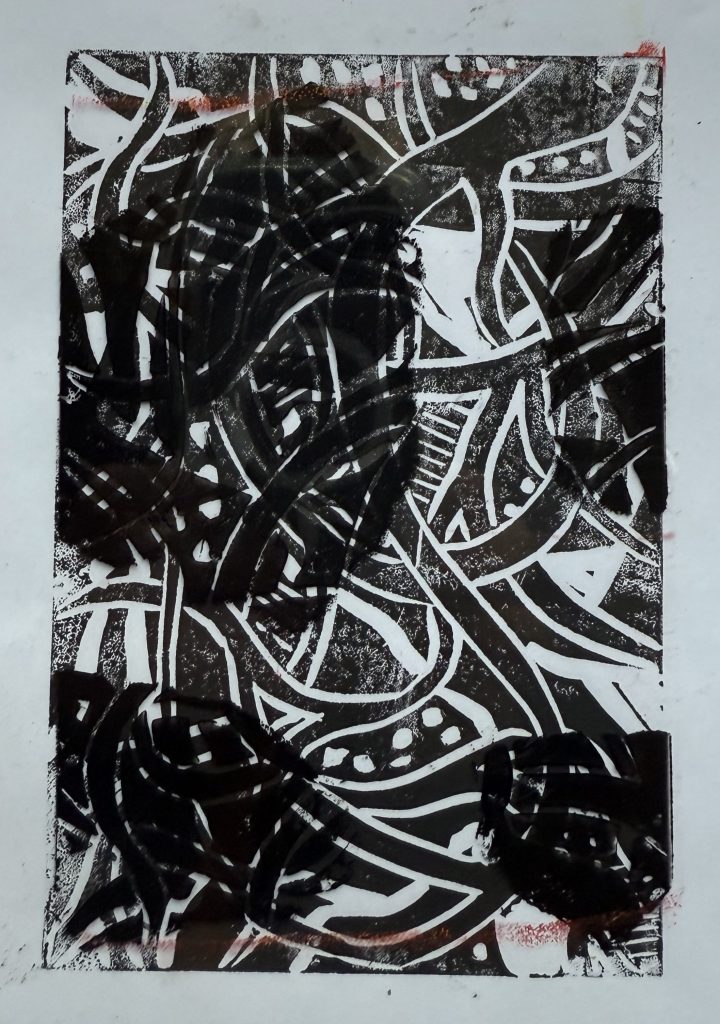

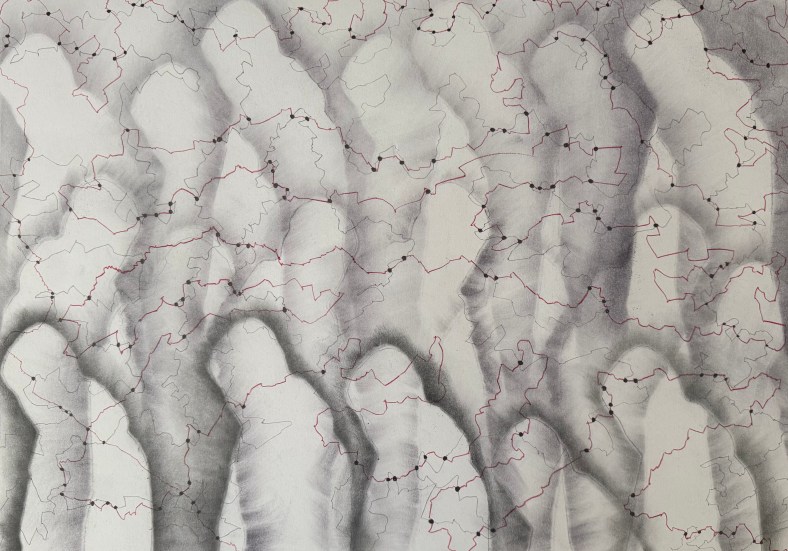

Cheng commented that the white shapes give the impression of something that is no longer there and the dark shapes are reminiscent of shadows. Thinking about it, the shadows are cast by something that is there but is not visible. A figure’s absence is felt yet we feel a figure’s presence somewhere – it just about sums up ancestry.

I explained the process of making the pieces and how they seemed to develop into a type of map. I mentioned that the subject of maps has come to the forefront of my thinking recently along with the idea of connection. In my Unit 1 feedback one of the comments was: “It feels as though you have been working through an abundance of techniques that are maybe a type of mapping – now is the time to compare and contrast all of those experiments in order to develop an intuitive and personal way of mapping your experiences…”.

For sometime I’ve been interested in Deborah Levy’s idea of her mother being her internal sat nav and I used Google maps to obtain the aerial image I used in Parental Loss. My art class recently gave me a scarf with a Grayson Perry map on it. I was thinking earlier in the year of mapping the course of a river. The coincidence that I chose to draw the lines in colours which reminded me of maps somehow has linked all of this together. That, and the fact that I have been complaining ad nauseum about not having a sense of direction.

During these two years, I am, to all intents and purposes, mapping my life.

There seems to be a strong unintentional link to maps in the images: Cheng said that the images in which I’ve marked the intersections remind her of constellations, and Dalal observed that the lines themselves could be interpreted as borders, which then feeds into borders marking the the point where countries connect. This led to me seeing that the outline of the shapes themselves resemble coastlines.

Cheng and Dalal both made some really helpful comments about potential development:

- playing with scale: a large image on a wall giving the impression of a map but then coming in close on a small scale to create a more personal experience and stronger connections

- Drawing on a vintage map or incorporating old family photos

- Using a pin to attach separate images to the points of intersection – this has since led me to think about criminal investigation maps – maps with string coming off from them to images and additional information on the perimeter

- Thinking about how I can use materials to create something that looks older, that comes from a past time – this brought to mind highly decorative old maps with sea monsters in the oceans

- creating a large scale reimagined map

Shortly after our session ended, I had a thought about making a digital map of my life with events or periods of significance being marked by specific points, a bit like a Google map, which you could then drag the yellow man to and drop into a space where you have a street view – maybe of images relating to that particular event. And then I laughed, Alexa laughed, Siri laughed, my husband laughed.

Lots to think about, as ever.